Ana Vidal Egea (El País) covers the new Wifredo Lam exhibition, “When I don’t sleep, I dream,” on view at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York from November 10, 2025, to April 11, 2026. [Also see our previous post Wifredo Lam: When I Don’t Sleep, I Dream.] Vidal writes, “His life, like his work, was complex and difficult to classify, which led him to be treated for a long time as a marginal figure within the history of Western art.” Here are excerpts. [Many thanks to Peter Jordens for bringing this item to our attention.]

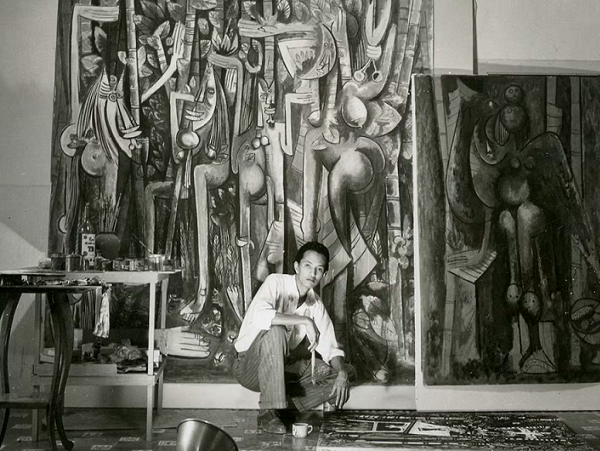

Eskil, one of the sons of Cuban artist Wilfredo Lam (1902-1982), notes that his father was at once well-known and not known. Lam’s life, like his work, was complex and therefore difficult to summarize and classify, which led him to be treated for a long time as a marginal figure within the history of Western art, despite being one of the pioneers of modernism. Now, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York wants to pay him the well-deserved tribute he never received in his lifetime. “When I Don’t Sleep, I Dream” is the first major retrospective of Lam’s work in the United States and the exhibition with which Christophe Cherix debuts as the new director of MoMA.

Although the Museum of Fine Arts in Havana refused to lend any works for the retrospective, the curatorial team has managed to assemble more than a hundred of Lam’s most significant pieces to reconstruct his artistic trajectory. The exhibition includes paintings, drawings, collaborations, books, and a short documentary about the artist. The main attraction is “Grande Composition,” Lam’s largest and most ambitious work (4.2 meters wide by 2.7 meters high), which has not been publicly displayed for 62 years and which the museum recently acquired from a private collector after several years of negotiations. This artwork sets it apart from other previous retrospectives of the artist’s work (at the Pompidou Centre and the Tate in 2015, and at the Reina Sofía Museum in 2016).

Lam, an example of the 20th-century transnational artist, described his art as “an act of decolonization” and his style evolved depending on the context. His life was not easy; among other tragic events, his first wife and eldest son died of tuberculosis. He was caught up in the civil war in Spain, where he had gone to study on a scholarship at the San Fernando Royal Academy of Fine Arts, and enlisted on the Republican side, guided by a moral obligation to fight against fascism. There he created The Civil War, his largest painting to date, commissioned for the Spanish Pavilion at the 1937 International Exposition in Paris. With Franco’s rise to power, he moved to Paris, where he befriended Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Joan Miró, and Max Ernst, among others. He painted tirelessly: “So much so that my small hotel room became full and I could barely move.”

Everything was going well; shortly after arriving in 1939, he had his first solo exhibition at the Galerie Pierre, where he displayed several works exploring motherhood. One of them, “Mother and Child,” was purchased by MoMA and became the first of Lam’s paintings to enter a museum collection.

But then World War II broke out, and with the German invasion of Paris, Lam was forced to flee to Marseille along with other artists. There, his friendship with André Breton deepened, and he became part of the Surrealist movement. He practiced Surrealism, he said, “to free himself from his worries and fears.” In 1941, at the age of 39, after being denied entry to the United States and Mexico due to his close ties with influential figures on the European left, he returned to Cuba, having spent nearly two decades in exile.

In 1945, MoMA acquired “The Jungle,” one of the first works Lam created upon returning to Cuba. It is a work in which the human is intertwined with the plant and animal. The painting is not done on canvas, but on kraft paper with diluted oil paint to make it last longer, as the artist had to devise creative ways to cope with the scarcity of materials.

The Jungle was displayed for many years in the museum’s lobby and became Lam’s best-known work. [. . .]

In Cuba, he reinvented himself, reconnecting with Afro-Caribbean histories, something that was greatly influenced by his friendship with the Cuban writer and ethnographer Lydia Cabrera. His work became imbued with symbolism and hybrid figures representing transformation, such as horse-women, plant-animals, and mutating birds. “I knew I ran the risk of not being understood by the average person or the general public, but a true work of art has the power to engage the imagination, even if it takes time,” the artist once remarked. [. . .]

For full article, see https://english.elpais.com/culture/2025-11-07/wifredo-lam-the-artist-who-bridged-the-caribbean-and-europe-finally-gets-major-retrospective-at-moma.html

Also see https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2025/nov/05/wifredo-lam-moma-exhibition

Wifredo Lam: When I Don’t Sleep, I Dream

November 10, 2025 – April 11, 2026

Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), 11 West 53 Street, New York, NY 10019

https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/5877

Ana Vidal Egea (El País) covers the new Wifredo Lam exhibition, “When I don’t sleep, I dream,” on view at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York from November 10, 2025, to April 11, 2026. [Also see our previous post Wifredo Lam: When I Don’t Sleep, I Dream.] Vidal writes, “His life, like