Located around Yokohama train station, there is an “especially unique watering hole”, specifically designed for customers who are contemplating quitting their jobs, said Japan Today.

At Tenshoku Sodan Bar, the bartenders are all trained counsellors, who offer impartial advice which you wouldn’t find from high-pressured friends and family, or unrelenting bosses who demand round-the-clock loyalty.

Though “job-hoppers” are still much less frequent in Japan than in Western countries, they are “on the rise”, said The Economist. The concept of a one-company-for-life worker – or “salaryman” – is “eroding”, as younger generations have “started to question this way of working”.

‘Resignation angst’

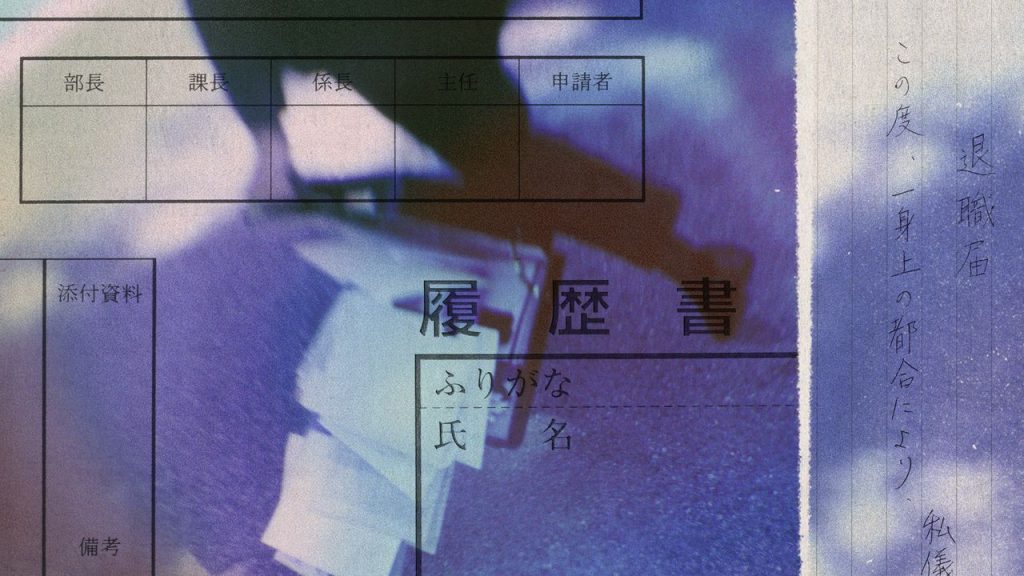

One “niche but increasingly popular” industry which helps workers break out from the “salaryman” cycle is “proxy quitters”, said The Washington Post. For a fee of up to ¥50,000 (£235), dissatisfied employees can hire someone to quit their job for them.

The service has boomed since the pandemic, with employees’ reasons including that they have been “bullied or harassed at work”, lack the nerve to confront their boss, or simply don’t know how to quit, as it is so rarely done. Nearly one in 10 Japanese companies have “received resignations via proxy quitters”, according to a 2024 survey by Tokyo Shoko Research.

This rise in proxy quitters has revealed a “darker side of Japan’s work culture” to the rest of the world, said CNA. Bosses often have “disproportionate power over employees”, which leads to the expectation of “long hours and unpaid overtime”. Workers are bound by the concept of “messhi hoko” – or “self-sacrifice for the public good” – which is “ingrained” in the Japanese working culture. The expectation to prioritise company needs over personal ones is often cited as one of the culprits for Japan’s declining birth rate. At its most extreme, it can “even be fatal”: the term “karoshi” refers to the phenomenon of “death by overwork”.

Proxy quitting services have emerged as a “direct answer” to these “intricacies of Japanese tradition and social conventions”, but their legality operates in a “grey area” and some employers argue they are “exceeding their authority”, said Leo Lewis in the FT. Even without legal challenges, however, the industry could peter out on its own. Predicated on “resignation angst” and a rigid workplace hierarchy, as office culture evolves, “demand will evaporate”.

Increased ‘leverage’

Evidence suggests that more and more people are defying traditional taboos and choosing to switch jobs, said The Japan Times. According to government data, around 940,000 people switched from one full-time employment to another in 2023, compared with 750,000 in 2018.

Changes in demographics are now working to young people’s favour, said The Washington Post. With a falling birth rate, “rapidly aging” population and “shrinking” workforce, employees wield considerably more leverage. Younger generations are less accepting of the excessively long days which are a “hallmark of Japanese corporate culture”. What was once the “revolutionary idea” of quitting for better terms is now a much more frequent possibility.

The numbers support this, said CNA. In the annual survey undertaken by the Tokyo Chamber of Commerce and Industry, 26.4% of young employees said they would “change jobs if given the chance”, while 7.6% planned to be self-employed in future.

Younger workers are also now more likely to claim the benefits which their employers are legally obliged to provide, said The Economist. “The share of men taking paternity leave has jumped from 2% of those eligible a decade ago to 30% in 2023.” More labour fluidity has caused Japan’s rigid payment structures to loosen, with salaries catching up with the rest of the world due to workforce demands. Though employers may be bracing for the impact of an influx of young, empowered workers, it could also “inject dynamism into Japan’s ossified institutions”.

Reluctance to change job and rise of ‘proxy quitters’ is a reaction to Japan’s ‘rigid’ labour market – but there are signs of change