Ten years after the Colombian writer’s death, and ahead of the publication of a lost novel, Rodrigo García opens the book on his father’s dementia, the daughter he kept secret and the time Mario Vargas Llosa punched him in the face.

A report by Helena de Bertodano for The Times of London.

Rodrigo García tells a funny story about his dying father, Gabriel García Márquez. One afternoon several nurses were standing at the foot of his bed discussing his care while García Márquez — who at that stage was “years deep into dementia” and close to death — was sleeping. “He wakes up, sees these four women and says, ‘I can’t f*** all of you!’ ”

Rodrigo — a taller, broader version of his father with beetling eyebrows, curly hair and a gentle manner — laughs as he describes the scene. “It was remarkable that a person so lost in time and space and knowledge still had a sense of humour. He had no idea where he was or who these people were, but he still knew that this would be funny.”

This April marks the tenth anniversary of the death of García Márquez, the Colombian author who in 1982 won the Nobel prize for literature. His most celebrated book, One Hundred Years of Solitude, which was published in 1967 and has sold more than 50 million copies, was described by The New York Times as “the first piece of literature since the Book of Genesis that should be required reading for the entire human race”.

A surprise “final” García Márquez novel, En Agosto Nos Vemos, or Until August, will be published next month to coincide with the anniversary of his death. One of Time magazine’s 25 most-anticipated books of 2024, it is, says Rodrigo, “about a woman who visits her mother’s grave every year and every year she has a different fling”.

Rodrigo, 64, says that he and his younger brother, Gonzalo, 60, had originally hesitated over its publication as their father, despite writing ten drafts, never felt it was quite finished. “My brother and I excuse ourselves,” Rodrigo explains, “because our father used to say, ‘When I’m dead, do what you want.’ We reread the book and thought it was much worthier than he thought. My theory is he lost the ability to judge the book.”

His father also felt that One Hundred Years of Solitude could not be translated to the screen, yet the brothers have given the green light to a Netflix adaptation, with the stipulation that it should be shot in Spanish in Colombia. “One of my dad’s problems was that it doesn’t fit into a three-hour movie with Al Pacino as [the principal character] Colonel Aureliano Buendía ”

Instead it is being released later this year as two seasons, each eight episodes long, 16 hours of screen time. “It’s very richly produced,” says Rodrigo, who has lived in Los Angeles for the past three decades and is an adviser on the production. He is married to Adriana, a teacher.They have two adult daughters, Isabel and Ines.

Rodrigo García, 64, at his home in Santa Monica

A successful Hollywood film and television director in his own right, Rodrigo is best known for the heartbreaking Nine Lives (2005), starring Robin Wright Penn, Glenn Close, Holly Hunter and Amanda Seyfried, and the period drama Albert Nobbs (2011), starring Close again. A few weeks ago Netflix released Familia (2023), his first Spanish-language film, a poignant portrayal of a Mexican family at a moment of crisis, faced with selling their olive farm.

Modest and unassuming, Rodrigo says his father worried that his fame would impede his children. In fact many people in the film industry are unaware of his parentage. “I was very determined to find my own way in the world,” he says. “And determined that being my father’s sonwas not going to be the main feature of my identity and would in no way paralyse me.”

His father, known by his friends and family as Gabo, had a pop-culture level of fame. “For a writer, he was like Mick Jagger,” Rodrigo says. “He’d go regularly to a local newsstand and people would pass out, like, ‘Oh my God, you’re here!’ ”

Yet for such a famous man, relatively little is known about his private life, which he guarded zealously. “Everyone,” García Márquez once told his son, “has three lives: the public, the private and the secret.” It is only in the aftermath of his death that some of his life outside the public eye can be pieced together.

A few years ago a whisper took hold that García Márquez had a secret child. In 2021 Rodrigo hinted at the rumour when he described the mourners at his father’s funeral in A Farewell to Gabo and Mercedes, a memoir dedicated to his parents: “For a moment it occurs to me that perhaps someone from his secret life could be among these people.”

Sitting in an Italian café near his home in Santa Monica, drinking an oat milk matcha latte, Rodrigo explains what he meant. “That was my secret wink to those who know ” He is referring to the fact that his father had a daughter, Indira. In the early Nineties a young Mexican woman called Susana Cato signed up for a screenwriting workshop that García Márquez was teaching in Cuba. A reporter for Cambio magazine in Mexico, she interviewed him and the two began a relationship. Soon after, Cato gave birth to their daughter, Indira, now in her early thirties, who took her mother’s surname. “As far as I know, he knew her as a child and visited her,” Rodrigo says. “But as he lost his memory, I’m sure he struggled to stay connected to her.”

Indeed, in his final couple of years he recognised almost no one. “He recognised my mum [Mercedes] as the main person, the alter ego, but I don’t think he knew her name. But he didn’t recognise my brother and me. Once, I remember driving back from a restaurant to the house and he was in the back with one of my daughters,” Rodrigo says. “And I could see him getting anxious that he was in a carful of strangers.”

García Márquez mobbed at Mexico City airport in 1981, having left Colombia because of his political views

Rodrigo vividly remembers the day his father told him and Gonzalo about their half-sister — just before Indira turned 18. It is unclear whether their mother ever knew of her existence. “We don’t know if she knew,” Rodrigo says. His first thought was for Indira herself. “My brother and I reached out to her because we were concerned that she thought we had been snubbing her her whole life.” They have since met many times. “She’s very nice. My brother and I have given her quite a few of my father’s personal effects, even though she has never asked for anything. Which is enough to endear you to her completely.”

By the time news of her paternity broke in 2022, Indira Cato had already established herself as a successful writer and producer of documentaries in Mexico. Her first, All of Me (2014) — about the women who feed the migrants clinging to La Bestia, the “death train” that travels from Central America to the US border — won an award in Mexico.

As far as Rodrigo knows, his father had no other children. “I’m sure someone would have appeared by now, looking for something,” he jokes.

Some secrets García Márquez has successfully taken to the grave, such as what prompted one of his best friends, the Peruvian novelist Mario Vargas Llosa, to punch him in the face in 1976.

García Márquez had run into his old friend at a film premiere in Mexico City. Delighted to see him, he exclaimed “Mario!” and stretched out his arms to embrace him. Vargas Llosa took one look at him and socked him in the eye. So began one of the greatest rows in literary history.

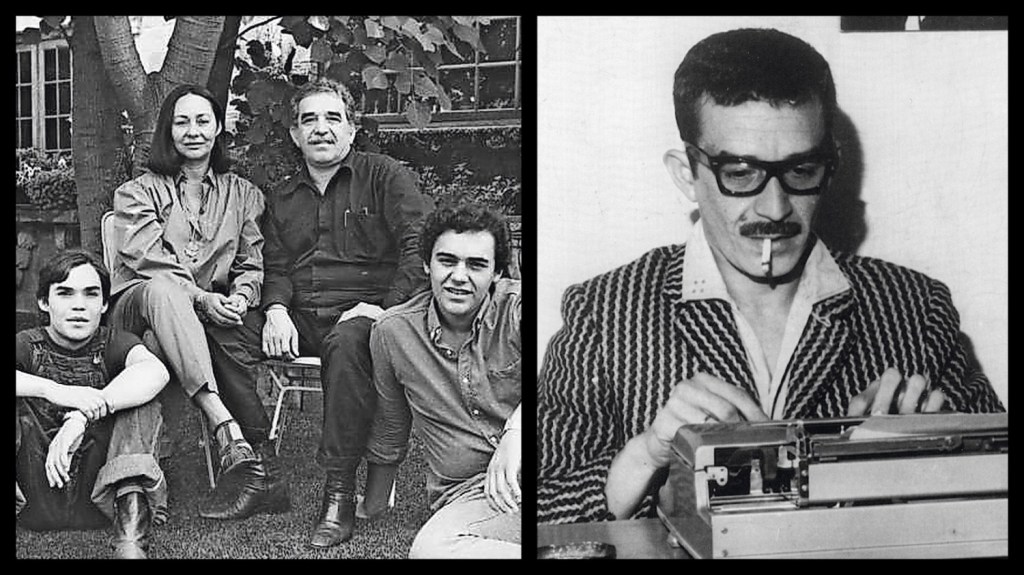

With the Peruvian novelist Mario Vargas Llosa in 1967

“I’ve heard versions,” Rodrigo says. “One was that Mario had left his wife, Patricia, for someone else. My parents had taken Patricia’s side. And whether that included my dad hitting on Patricia, I don’t know. But in fairness it was all gossip.”

The two writers never spoke again. “I never cared to ask because it was not a good subject,” says Rodrigo, who remembers well the years when his father and Vargas Llosa were close. “They lived a block away from us in Barcelona. We used to go on these big Sunday lunches, very Spanish style. His kids were younger than us and one of them is named after us: Gabriel Rodrigo Gonzalo[the first names of the three García Márquez men].”

Although great friends, they were very different writers and used to have lively debates about art and literature. “Mario was very much an artist and an intellectual,” Rodrigo says. “My dad was just an artist; he read only what he liked. For example he never liked Proust and said Remembrance of Things Past was the most boring, Frenchified thing he’d ever read.”

He was also dismissive of his own work, especially One Hundred Years of Solitude. “He came to hate the book, because for years it was One Hundred Years this, One Hundred Years that. And it was a hard act to follow. He would refer to it as ‘la pinche novela’ — ‘that f***ing novel’ But the success of Love in the Time of Cholera [his story of love and ageing, which came out in 1985, three years after he won the Nobel] reconciled him with One Hundred Years … I think towards the end, he forgave it a little more.”

Whatever transpired, Rodrigo thinks that his father and Vargas Llosa wanted to patch up their differences. “If not for the wives there would have been a rapprochement,” he says. “That’s me speculating, but at some point in the 2000s they were sending smoke signals to each other. But I think the two wives killed it.”He adds, “My dad and Mario knew of course [what really happened]. Or one of them knew. Or Mario thought something had happened and it hadn’t.”

I once interviewed Vargas Llosa and asked him directly why he had punched his friend. “I don’t ever talk about that,” he said. Now, 87, he published what he has said will be his final novel, I Give You My Silence, last year.

A few weeks later I meet Rodrigo again, this time at his home, a beautiful Spanish Colonial-style house in Santa Monica. His wife, Adriana, waves cheerfully from the garden, where she is pruning a tree, and Rodrigo points out the guesthouse where his parents used to stay on their frequent visits. Family photos show his father looking dapper in designer boots. “He wanted to be taller, so he always wore these Italian boots.” On a bookshelf is a puppet version of García Márquez. “It used to make him laugh,” Rodrigo says, taking it down. “It’s the kind of thing they sell at the market in Colombia.” A candle bears his portrait as an angel with wings, under the words “Saint Gabriel”, which one of Rodrigo’s daughters found on Etsy, an indication of how deeply García Márquez is revered, especially in Colombia, where he was born, and in Mexico, which he made his home.

Rodrigo at home with a portrait of his father, who was once described as “the greatest Colombian who ever lived”

Born in 1927 in the small town of Aracataca, near Colombia’s Caribbean coast, García Márquez was left by his parents in the care of his maternal grandparents for his first eight years — after his father, a postal clerk and telegraph operator, took a better job in the city of Barranquilla. The author often described these years as the happiest of his life and he was strongly influenced by both his grandmother, who was fiercely superstitious and believed in ghosts and miracles, and his grandfather, who would regale him with stories of his heroic exploits as a colonel in the Colombian War of a Thousand Days.

Later he studied law in Bogota, where he also began his career as a journalist during La Violencia, the savage ten-year civil war that ran from 1948 to 1958. He interspersed this with writing poetry and short stories, eventually publishing Leaf Storm in 1955, a novella in which the fictitious town of Macondo is introduced — based on Aracataca, it later formed the backdrop of One Hundred Years of Solitude.

Here he experimented with some of the techniques, such as manipulation of time, that are the essence of magical realism — the combination of a realistic narrative with fantasy, a style that defined his work. But he intensely disliked the magical realism label as he felt he was describing life as it actually was in small town Colombia. “Most of it actually happened,” Rodrigo says.

On the little finger of Rodrigo’s right hand he wears two simple silver rings. He twists them off and hands them to me so I can read the inscriptions inside: they are his parents’ wedding rings, inscribed in tiny writing with their names, Gabriel García and Mercedes Barcha, and the date of their wedding: March 21, 1958. They had originally met as children in the 1930s in Sucre, a town in northern Colombia where Barcha’s father was a pharmacist. García Márquez knew immediately that he wanted to marry her one day. “My father always said she was the most fascinating person he had ever met,” Rodrigo says.

Rodrigo was born in 1959 in Bogota; two years later, dismayed at Colombia’s political climate, García Márquez moved his family to Mexico City, where Gonzalo was born in 1964. Having made a point of criticising corruption in the Colombian government, García Márquez had become a controversial figure in the country and spent most of the rest of his life in self-imposed exile.

An undated family picture

Rodrigo remembers his father working “trance-like” on One Hundred Years of Solitude — the multigenerational story of the Buendía family — in Mexico. Sometimes his mother would send him and his brother into his father’s study with a message. He would look right through them, registering nothing, “lost in a labyrinth of narrative”.

As a child, Rodrigo did not realise how little money his parents had. “Looking back, our house was quite empty. We had a couple of rooms with no furniture. I do remember a Christmas where we came down and there was an enormous amount of gifts. I asked my dad about that many years later and he said, ‘Friends knew we were struggling and they sent gifts.’ ”

While his father wrote, his mother arranged lines of credit from the butcher and dealt with the landlord: “My parents didn’t pay rent for 11 months.” When the manuscript was finished, his mother pawned her hairdryer to pay for the postage. “Her parting words were, ‘It had better be good.’ ”

Upon publication, the book achieved rapid success and was translated into English in 1970. The family moved to Barcelona for several years where his parents were “extremely gregarious”, Rodrigo says, with a large circle of friends including the Mexican writer Carlos Fuentes and the Spanish film-maker Luis Buñuel. “Buñuel was like a Spanish uncle. But you know what it’s like when you meet these big artists. It’s not like poetry is flowing from them. They’re just worried that the soup is hot.”

With, among others, the Spanish film-maker Luis Buñuel, seated second left, in 1965

As a family they were especially close. “The rest of the family on both sides was in Colombia, so we had a strong sense of the four of us as a unit, a club of four.” Rodrigo attended English-speaking schools in both Mexico City and Barcelona, then studied history at Harvard. His parents, he says, were the antithesis of helicopter parents. “They came to my school twice in my life.” But they would have lunch as a family every day of the week. “My dad always demanded that we came home for lunch Latin-style at three in the afternoon after school so he could interrogate us, ‘How’s life, what’s going on ?’ ”

In the late Seventies they started to spend long stretches of time in Cuba, where García Márquez developed a close friendship with Fidel Castro, who would sometimes come to stay. “It was a bit of a mystery where Castro slept,” Rodrigo says. “His security detail would call to ask my dad if he was going to be at home that night. My dad would say yes and they would say, ‘You might have a visitor.’ And ‘might’ meant ‘might’. And it could mean at 10.30pm or 1.30am.”

By the Eighties his father was so famous that, as Rodrigo puts it, “all you had to do for the phone to ring in our house was to put down the receiver”. He recalls an outing with his parents in New York a few years later. “Two middle-aged Argentinian women screeched and threw themselves at him and covered him with kisses. Practically impregnated him. When we walked on, my mum was, like, ‘What the f***? I’m standing there and these women are kissing my husband!’ ”

What about your father, I ask. What did he make of it? “Oh, please.” Rodrigo chuckles. “Women kissing him?” He shrugs and turns his palms up, showing that his father had no problem with female attention.

García Márquez with Fidel Castro, a frequent house guest

“The view from 80 is astonishing, really,” García Márquez told his son once. “And the end is near.” “Are you afraid?” Rodrigo asked him. “It makes me immensely sad,” his father replied. He was beginning to lose his mind by then and agonisingly aware of it. Once, Rodrigo says, the housekeeper found him in the garden and asked him what he was doing. “Crying,” he replied. “Don’t you realise that my head is now shit?” He would reread his old books without knowing who the author was. “Later he would see his picture on the cover and say, ‘Oh, that’s my book? I’d better start it again.’ ”

His father would never attend a funeral, saying he did not want to bury his friends. He died in 2014, aged 87, of pneumonia. Rodrigo shows me a photograph of his father’s body wrapped in a sheet before cremation, yellow roses — the flowers his father loved — placed on top. “I remember seeing my dad minutes after he had died and thinking, ‘I can’t believe that life ends.’ It’s such a silly thought.”

The ceremony held in Mexico City following his death was almost a state occasion . Thousands of people filed past the urn containing his ashes. The Colombian president, Juan Manuel Santos, paid tribute to him as “the greatest Colombian who ever lived”, while the Mexican president, Enrique Peña Nieto, enraged Rodrigo’s mother by referring to her as “the widow”. “No soy la viuda,” she told her sons later. “Yo soy yo.” (“I am not the widow. I am me.”)

She died six years later, in 2020, at the height of Covid. The last time Rodrigo saw her was through a cracked phone screen. “The death of the second parent,” he writes in his memoir, “is like looking through a telescope one night and no longer finding a planet that has always been there.”

Now that both his parents have gone, Rodrigo wishes he had asked them more “about the fine print of their lives”, especially their childhoods. “I think about the remote places in Colombia they came from. And how they ended up adapting to a world of fame and fortune There’s a parlour game where you choose to have dinner with any historical figures. If I could choose, I would only have dinner with my parents in their forties. I can’t even think of a third person.”

As for the secrets his father took to the grave, Rodrigo tells a remarkable story about how his father paid his mother to return all the letters he had written her before they were married. “He bought them from her for 500 Colombian pesos at the time,” he says. Most surprising of all, this was in the late Fifties, long before he became famous. So why did he do it? “Go figure,” Rodrigo says. “Who would care? But I guess he cared. We live in an age where everything is public. And I think it’s OK that some things will never be known.”

Familia is streaming on Netflix. Until August by Gabriel García Márquez (Penguin £16.99) is published on March 12. To order a copy go to timesbookshop.co.uk. Discount for Times+ members

Ten years after the Colombian writer’s death, and ahead of the publication of a lost novel, Rodrigo García opens the book on his father’s dementia, the daughter he kept secret and the time Mario Vargas Llosa punched him in the face. A report by Helena de Bertodano for The Times of London. Rodrigo García tells