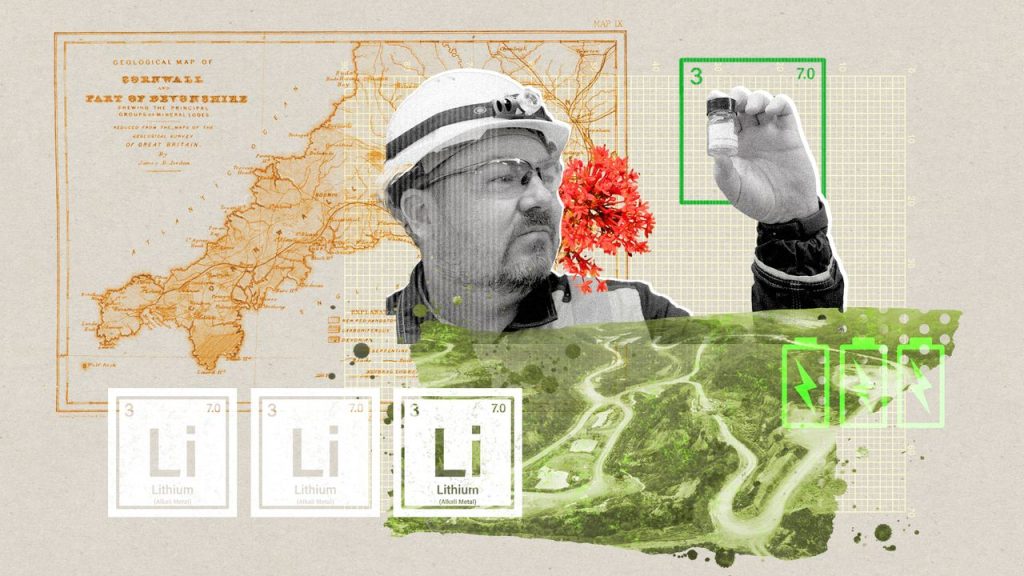

Minerals are a hot topic in 2026. Lithium, the crucial ingredient in batteries that power smartphones and electric vehicles, is in particular demand. While most of the discussion has been around the potential treasure troves of Greenland or Ukraine, Cornwall is believed to sit on the largest lithium deposits in Europe.

Mining company Cornish Lithium made a “major production breakthrough” last October, said The Telegraph: it produced lithium hydroxide, a raw material required to make lithium-ion batteries. “It is believed to be the first time lithium hydroxide has been produced in Britain outside of a laboratory.”

Cornwall’s ‘roaring future’

If the world is ever to get close to net zero, lithium will be at the centre of it, said The Times. It can store more energy than most elements and is ideal for rechargeable batteries. That means it is playing an “increasingly important role” in the energy system. When “hooked up to a grid”, batteries can “absorb renewable energy when it is abundant and release it when scarce”.

The world has developed a “sudden and ravenous appetite” for lithium. That demand is expected to triple over the next decade as the green transition accelerates, said the International Energy Agency.

“Lithium is now among the most important mined elements on the planet,” said The Guardian. Most is extracted in Australia, the so-called lithium triangle in South America (Chile, Argentina and Bolivia), and China. The latter also “processes and therefore controls a majority of it for use in batteries”.

Cornwall doesn’t compare in scale but it is “probably the largest lithium deposit in Europe”. Cornish Lithium and another company, British Lithium, are “leading the way to tap into it”. And as the race to secure critical minerals intensifies, “there’s renewed enthusiasm for domestic exploration projects for critical minerals”, said Jamie Hinch on The Conversation.

In September, the National Wealth Fund announced a £31 million commitment to Cornish Lithium. And last month, the government released its critical minerals strategy, which could be a “watershed moment” for Cornwall, said Cornwall Live. The promised funding could be a “huge boon for the Cornish economy not seen since the heyday of tin mining”.

‘Supply chain dominated by China’

The “reshoring of mining” back to Britain can mitigate the “decline of employment opportunities” through the loss of industry, said Hinch. Cornish Lithium said it will create more than 300 jobs over the Trelavour Lithium Project’s 20-year operation, and 800 during construction. There is a “tempered optimism” that lithium could “rejuvenate” the county, which has some of the most deprived areas in the UK.

Cornwall’s “mining renaissance” extends beyond lithium, said The Economist. Britain’s last tin mine, South Crofty, near Redruth, has been dormant for nearly 30 years. It is now “being resuscitated by Cornish Metals” and is scheduled to resume operations in 2028, as the only mine in Europe that primarily extracts tin. The Trump administration said this month it was willing to loan up to $225 million (£165 million) to support the reopening, for some of its output in return.

Cornwall’s mineral deposits also present political opportunities, said Politico. Labour MPs are “betting” that local development of lithium mines – not to mention copper, tin and tungsten – will “help them keep their seats” at Westminster.

But China still looms on the horizon, said Politics Home. The superpower “produces more than 50% of 17 of the top 27 critical mineral groups, and refines 90% of the world’s rare earths”. It controls “critical mineral extraction on five different continents”.

Though the UK could initially bypass China by refining lithium “on home soil”, it would still be “entirely dependent on a global supply chain dominated by China”, said The Times. Once lithium has been refined, it needs to be turned into a battery cathode, and “almost 90 per cent of cathodes are made in China”.

But if Britain found a way to circumvent this step, such as piggybacking on “plans for several” commercial cathode facilities in Europe, it could capitalise on the manufacturing of battery cells on its own shores. To that end, processing gigafactories are expected to open in Sunderland and Somerset next year.

Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy