They say the Devil is in the details but they have been saying it only since the late 20th century, according to the Oxford Dictionary of Phrase and Fable.

It’s possible that the devilish phrase was coined in response to its predecessor, which espouses quite the opposite sentiment. The great architect and designer Mies van der Rohe (1886 to 1969) is credited with being the first to express that “God is in the details”.

Still, one of the revealing peculiarities of phraseology and idiomatic usage is how the dark forces often have the best lines. That complaint was registered as far back as the 18th century by Rowland Hill (1744 to 1833), an English evangelist who plaintively remarked: “Why should the Devil have all the best tunes?”

Singer and composer Chris de Burgh’s song Spanish Train echoes that practice and exudes existential despair that Christ is no match for the ruthlessly strategic and cheating Devil, whether at cards or chess, in both cases playing for the souls of the dead.

A sample verse: “And far away in some recess / The Lord and the Devil are now playing chess / The Devil still cheats and wins more souls / And as for the Lord, well, he’s just doing his best.”

The song provoked global outrage in many quarters when released in 1975, a reaction unlikely to be repeated today, in a world far more secular, far less believing and with an even smaller smidgeon of spirituality and religious faith. (A local footnote — Spanish Train remained banned from the airwaves and for sale on both LP and seven single for quite some time in South Africa.)

It is not only in lyrics that the Devil seems to outscore the forces of light and good. In literature, call him Lucifer, Satan or the Devil, the diabolic one has seized the poetic and prose imaginations of writers.

Lucifer, bearer of light, from the Latin “light-bringing morning star”, is the rebel archangel whose fall from heaven gives the human world the Devil or Satan.

And it’s from the Hebrew satan (adversary, derived from satan as in plot against) via late Latin and Greek that English has Satan. Hebrew usage in the Old Testament, however, generally signifies a human opponent.

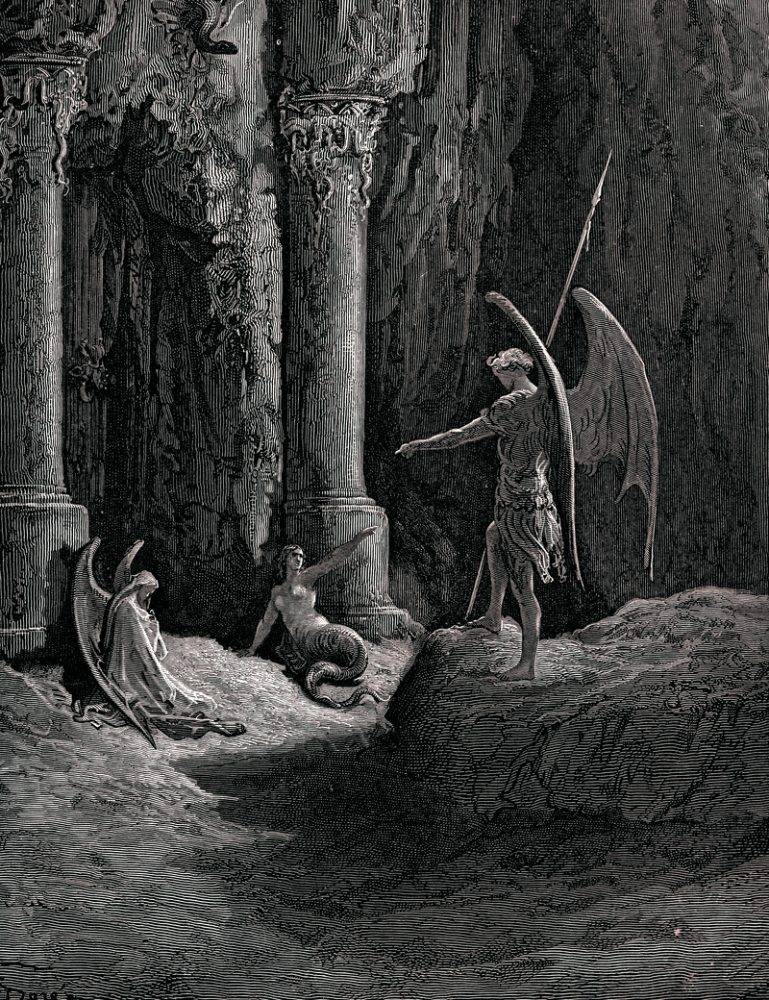

Arguably there is no more profound a description of Lucifer’s fall than in John Milton’s epic poem Paradise Lost. Book 1 sets out the subject of the poem, human disobedience, and its consequences: the fall of Adam and Eve from Paradise, engineered by the serpent or, more accurately, Satan in the serpent.

Milton asks that he “may assert eternal providence, / And justify the ways of God to men.”

A few lines later, the poet describes Satan, “whose guile / Stirred up with envy and revenge, deceived / The mother of mankind, what time [needlessly] his pride / Had cast him out from heaven, with all his host / Of rebel angels, by whose aid aspiring / To set himself in glory above his peers, / He trusted to have equalled the most high, / If he opposed; and with ambitious aim / Against the throne and monarchy of God / Raised imperious war in heaven and battle proud / With vain attempt.”

Milton, though, is not wholly tempted by proud Lucifer. In equal depth, he describes God’s reaction: “Him [Lucifer] the almighty power / Hurled headlong flaming from the ethereal sky / With hideous ruin and combustion down / To bottomless perdition, there to dwell / In adamantine chains and penal fire, / Who durst defy the omnipotent to arms.”

Lucifer, the irredeemable rebel, vows that “All is not lost; the unconquerable will, / And study of revenge, immortal hate, / And courage never to submit or yield: / And what is else not to be overcome?”

So begins the eternal struggle between good and evil, with humankind, now stained by sin, as both its medium and its battleground.

Milton draws his great poem to a close thousands of lines later, with humankind’s metaphorical ancestors leaving Paradise and about to take their first timorous steps on the Earth: “Some natural tears they dropped, but wiped them soon; / The world was all before them, where to choose / Their place of rest, and providence their guide: / They hand in hand with wandering steps and slow, / Through Eden took their solitary way.”

Succumbing to the Devil by yearning for the power and knowledge of God, just as did Lucifer, is the subject of Christopher Marlowe’s sublime play Doctor Faustus. Despite all his accomplishments as physician and scholar, Faustus is still not content. He poses the “problem” and shows the God-like ambition that sent Lucifer to perdition and will do so also with him.

“Yet art thou still but Faustus, and a man. / Couldst thou make men to live eternally, / Or, being dead, raise them to life again, / Then this profession were to be esteemed.”

Faustus strikes a bargain with the satanic agent Mephostophilis (Marlowe’s spelling) for 24 years of knowledge, power and pleasure in return for his soul. But he is traduced, granted only “showbiz” insights into the world, and never attains the divine knowledge he seeks.

When the time comes to pay the account — a great reckoning taken in his study — Faustus realises the enormity of his ambition, his sin, and the terrible fate that awaits in hell.

“The devil will come, and Faustus must be damned. / O I’ll leap up to my God! Who pulls me down?”

And a very short while later: “All beasts are happy, for when they die, / Their souls are soon dissolved in elements; / But mine must live still to be plagued in hell.”

Then, enter Lucifer, Belzebub (sic) and sundry devils: “My God, my God! Look not so fierce on me! / Adders, and serpents, let me breathe awhile! / Ugly hell gape not! Come not Lucifer; / I’ll burn my books — ah Mephostophilis!”

Off they go with the fallen scholar and the Chorus intones: “Cut is the branch that might have grown full straight, / And burned is Apollo’s laurel bough, / That sometime grew within this learned man.”

Apollo is the Greek god of prophecy, poetry and music. He is the god of the lyre and the bow (archery) and of feasting and sickness and health. He takes us from the Christian world of God and Satan to that of the Olympian gods, presided over by Zeus and an altogether different relationship with humans.

The gods intervene actively in The Iliad on behalf of the humans they favour. Apollo fights on the side of the Trojans, as does his half-sister Aphrodite, the goddess of love. (Their father is Zeus but they have different mothers, Leto for Apollo and Dione for Aphrodite.)

While Apollo is the chief protector of the Trojans, Zeus shows them great sympathy too, partly out of the human-like motive of irritating his wife Hera (latinised from Here), who lends the Achaians (“Greeks”) her full support. On the Achaian side too is Athene, also called Pallas Athene, and Tritogeneia, the daughter of Zeus, whose mother Homer does not name.

The scholar, translator and founder of the Penguin Classics series EV Rieu beautifully explains the gods of The Iliad in the introduction to his translation of the poem. This was the volume that launched Penguin’s astounding publishing venture, which democratised the classics for a post-World War II reading public, and made great literature in languages other than English available at bargain prices.

Rieu writes: “Homer then reveres his gods, but rightly feels it would be untrue to life to make these formidable creatures take one another as seriously as he takes each of them.

“They are members of a family, and, as such, are all on much the same level, like the members of a human family, the father of which may be a terror to his office-boy but fulminates with less effect at home.

“Thus, for a realist like Homer, high comedy in Heaven was artistically inevitable.”

Deep humanness was also inevitable in Homer’s depiction of the gods. It must have been endlessly encouraging for those listening to Homer’s poem to hear the following and it is as cheering to those reading it today:

“So speaking, the son of Kronos [Zeus] caught his wife in his arms. There / underneath them the divine earth broke into young, fresh / grass, and into dewy clover, crocus and hyacinth / so thick and soft it held the hard ground deep away from them. / There they lay down together and drew about them a golden / wonderful cloud, and from it the glimmering dew descended.” (From The Iliad, Book XIV, translated by Richmond Lattimore.)

The battle between Satan and the forces of good has preoccupied writers for aeons