Here’s a fascinating opinion piece by artist Coco Fusco for Hyperallergic. Writing about a letter she received from Carl Andre about Ana Mendieta, she writes, “He copyrighted the letter and ended it with “for your eyes only,” as if to say, don’t even think of showing this to anybody.”

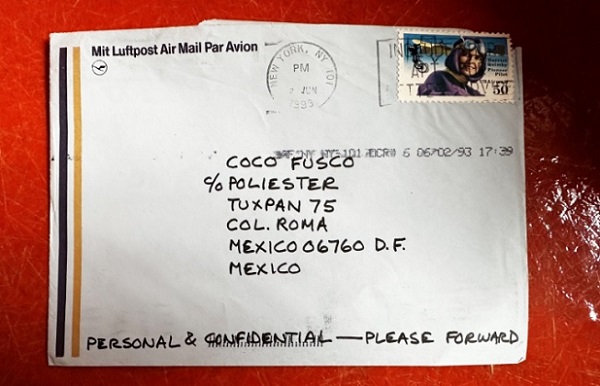

About 30 years ago, Carl Andre, who died in January, wrote me a letter. It was in response to an article I had written about Ana Mendieta. He wrote his message by hand, using the block letters that are a hallmark of his personal correspondence; but he didn’t know me. I had no idea how he found me, but he let me know that his message was for me and only me: He marked his letter “personal and confidential,” put a copyright sign on it, and ended it with “for your eyes only,” as if to say, don’t even think of showing this to anybody. For years, I was too afraid to mention the letter in public, imagining that he might take revenge. I had heard plenty of scary stories about Mr. Andre from Mendieta’s close friends. I had never met him, but I knew he was a famous White male artist who might also be a murderer.

Before I received that letter, I had imagined the scene on that fateful night in 1985 in his Mercer Street apartment a million times: the liquor-filled fridge, her furtive whispers about divorce on the phone with a girlfriend, his massive figure sinking into a sofa with a drink in hand, her taunts, his grunts, the window ledge that came up to her chest, the sound of her screaming “No!” filling the air as she fell.

Andre knew how to throw his weight around. He had the power, the money, and the connections to walk free. And he had done so after Mendieta’s relatives and friends sat in a courtroom for days listening to a lawyer conjure a portrait of his dead wife as a suicidal Cuban freak. He was White masculine supremacy incarnate. As far as I was concerned, what I wrote about her had nothing to do with him. But by insinuating himself into my life with that letter, he made me feel as if I had done something wrong. [. . .]

After Mendieta’s first retrospective at the New Museum in 1987, I wrote about her work and what making art in Cuba meant to her. I loved the visceral quality of her performances and admired her defiance. She created work in the nude, which was nothing short of scandalous for straightlaced Cuban-exile Catholics; she embraced Afro-Cuban ritual as a source for her practice, even though she hailed from an upper-class White Cuban family; she returned to the island even though the Communists who had imprisoned her father were still in power; and she made fun of Americans’ stereotypical views of her culture by calling herself “Tropic-Ana.” She was a badass, and I was a 20-something who wanted to be like her. She had also befriended a group of iconoclastic young artists in Cuba who were stirring up trouble by throwing the rules of revolutionary art to the winds. They wanted to know about the New York art scene that Cuban apparatchiks deemed an expression of “Western Imperialism,” and she became their informant. I met those artists after her death in 1985. They were still in shock at her passing. Even though Andre had footed the shipping bill for sending artworks by US-based artists to the Havana Biennial in 1986 — which I took to be a gesture of remorseful generosity — they cursed him. As I began to travel to Cuba and developed friendships with those artists, I felt that in some way, I was following Mendieta’s lead. [. . .]

Eight years had passed since Mendieta’s death, but he felt some need to share his thoughts with me. And so, he let me know that I had truly understood her relationship with Cuba, which, he called “her lost Eden.” His letter was brief. He didn’t mention her death, nor did he consider any of her work. He instead focused on his view of her emotional life as an exiled Cuban who had been separated from home and family as a child. I am the daughter of a Cuban exile, and I grew up among people mourning the loss of that same homeland on a daily basis, so it wasn’t hard for me to grasp why the traumatic loss was so important to Mendieta. What irked me was Andre’s need to tell me about it. I felt like he was stepping on somebody else’s turf. Hers. Mine.

Why did I have to know what he thought? Why did he want to tell me? Did he think I needed his approval of my interpretation of her relationship to her country? Was he looking for mine because I am Cuban American? [. . .]

It bugged the hell out of me that Andre sought to define Mendieta’s relationship with Cuba and call it “her lost Eden.” The Bible is not exactly what I would use to describe Cuba. Childhood trauma can influence the work of any artist, but Cuba was hardly a paradise for Mendieta, even if her early childhood was a happy and comfortable one. [. . .]

For full article, see https://hyperallergic.com/876490/that-time-carl-andre-wrote-coco-fusco-a-letter/

Here’s a fascinating opinion piece by artist Coco Fusco for Hyperallergic. Writing about a letter she received from Carl Andre about Ana Mendieta, she writes, “He copyrighted the letter and ended it with “for your eyes only,” as if to say, don’t even think of showing this to anybody.” About 30 years ago, Carl Andre, who died