To be a cultural activist means striving for authentic expression, humility and responsibility — and not just in words. Such cultural work demands proactive efforts to teach and reach audiences near and far.

It’s the pride a nation has in their cultural identity and heritage that makes all the difference for such activists.

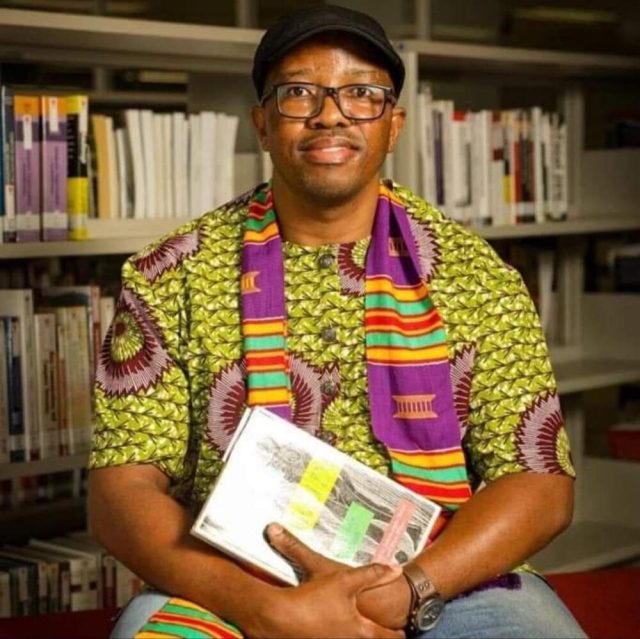

Sepedi poet and cultural worker Moses Seletisa’s work is rooted in both cultural responsibility and the need to ensure South Africa’s linguistic heritage survives and evolves.

“As an indigenous writer, I see it as my duty to preserve and promote languages like Sepedi.

“Language is more than a communication tool — it carries our identity, history and knowledge.

“Just as a geographer defining the concept of ‘sustainable development’, I believe in using and protecting our languages for future generations,” says the Limpopo-born poet.

Seletisa discovered his love for poetry at 15 years old when he wrote his very first poem, titled University of the North, dedicated to the late Professor John Ruganda, who was then teaching creative writing at what is now the University of Limpopo. He had the honour of writing and performing the poem during Herifest, the largest performing arts platform in what was then Northern Province, now Limpopo.

“That was the moment that ignited something deep within me. It was then that I felt a true calling to refine my craft and grow as a native poet.”

Since then, Seletisa has built a burgeoning career penning poems and short stories in his home language, Sepedi.

His language activism has earned him numerous accolades. His poem Mahlalerwa, for instance earned him a Sol Plaatje European Union Poetry Award in 2017, the first recipient writing in a language other than English or Afrikaans.

He penned Tshutshumakgala in 2015, a Sepedi biography of the struggle stalwart Tlokwe Maserumule, which earned him a South African Literary Award.

This week, Seletisa received yet another accolade — the Avbob Poetry Anthology Award for single authors for his first poetry collection, Di a Galaka. Of this, he modestly says accolades are “like flowers in my special garden”.

He cites sage advice from one of his mentors, Goodenough Mashego, who says he should focus on producing good writing, rather than chasing fame or popularity.

“And I believe my mentor has a point. When you study writers like [Zimbabwean novelist and short story writer] Dambudzo Marechera for instance, you see someone who poured everything into the work itself — unfiltered, raw, honest — without trying to fit into any literary mould or trend.

“That’s the kind of authenticity I aspire to. If the writing is honest, the recognition will follow in its own time.”

Writing purely in one’s home language does come with its hurdles for young writers, however, even in one’s native country. A key challenge Seletisa has had to overcome was while writing the biography Tshutshumakgala. At the time, he lacked the financial resources to conduct thorough research — he didn’t even own a cellphone.

“I relied on public phones to reach out and follow up on my research.

Tlokwe, the subject of the biography, was a full-time member of parliament, based in Cape Town, and his demanding schedule made it hard to secure regular interview sessions.

“Writing the book was both a challenging and life-changing experience,” he adds.

The breakthrough for Seletisa came when Tlokwe made the generous decision to fund the book.

“He used his personal savings to sponsor a 90-day research trip for me to go to Cape Town. Looking back, Tshutshumakgala was more than just a biography — it was a lesson in persistence, humility and the power of community support,” he says.

As a self-taught writer, such community support and relationships are certainly needed. Thus, mentorship, Seletisa says, served as a catalyst for him to grow as a writer over the years.

He praises the literary brilliance of Professor David wa Maahlamela and the late poet and musician Matete Motsoaledi, and their guiding force in cultural activism.

“Dr Puleng Nkomo, whose dedication to the arts also offered many of us opportunities to thrive, and the late Madame Aletta Motimele, whose nurturing presence and support for young talent left an unforgettable mark. Their contributions laid the foundation upon which I continue to build my voice as a self-taught author,” Seletisa says.

Though the South African government and mainstream media lags behind in promoting our indigenous languages, Seletisa acknowledges the efforts made.

His work has also appeared in popular shows like SABC 1’s youth daily drama Skeem Saam.

“I love that show. They’re doing an incredible job promoting our indigenous languages, especially in a space where linguistic representation often gets sidelined. It also reminds me of the earlier days of Muvhango, when they used to feature full poetry segments,” he says, enthusiastically.

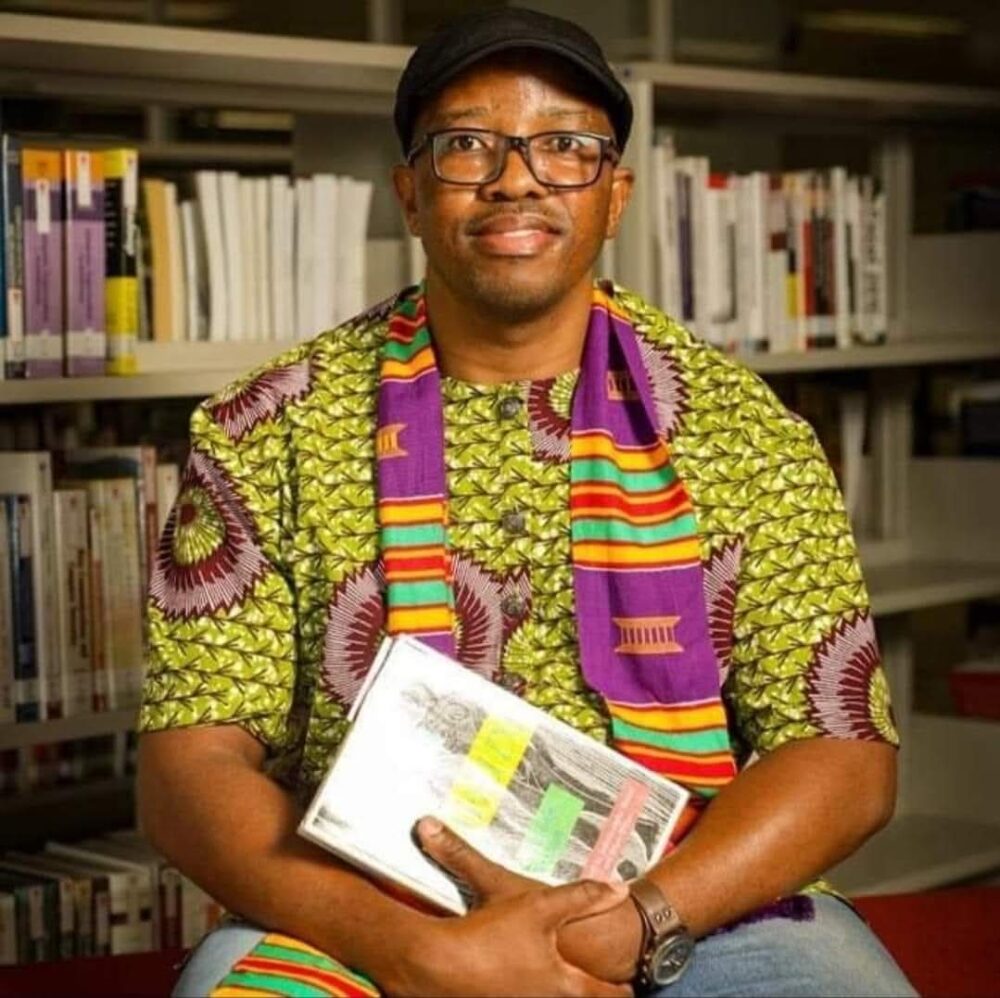

Another prolific writer actively promoting writing in his mother tongue is award-winning author Sabata Mpho Mokae. Purely writing in Setswana, Mokae has given readers three award-winning novels: Ga ke Modisa (2012), Dikeledi (2014) and Moletlo wa Manong (2018).

All three have been the subject of postgraduate studies at various universities. His most recent novel Lefatshe ke la Badimo promises to be no different.

Mokae’s writing journey started with the English language, when he was a journalist, before he transitioned to writing in Setswana.

When penning the accessible biography The Story of Sol T. Plaatje in English in 2010, he was inspired by Plaatje’s work on the importance of preserving African languages.

Mokae abandoned his initial manuscript of Ga ke Modisa, which he was writing in English. Writing novels in Setswana allowed him to authentically express the emotions of his characters, using Setswana phrases, which felt more natural.

“I’ve been writing in translation but writing in Setswana I had a sense of freedom. My late uncle Dr Gomolemo Mokae used to call it freedom of the tongue.

“So, I gained freedom of the tongue and that sense of freedom made me not to even imagine myself writing a novel in English because it was such a joy to write in my first language.

“I no longer have to negotiate with English as a middle man when writing stories.”

Working as a creative writing lecturer at Sol Plaatje University in Kimberley, Northern Cape, Mokae says he was inspired by several authors and their works. In South Africa it was the likes of his uncle, Es’kia Mphahlele, and Sol Plaatje, whose 1916 English novel Native Life in South Africa directly influenced Lefatshe ke la Badimo.

West African Chinua Achebe’s book No Longer at Ease (1960) was the first to make Mokae imagine himself as a writer.

Across the Atlantic, Mokae was profoundly influenced by Toni Morrison’s work, particularly The Bluest Eye (1970) and Beloved (1986). The two novels, Mokae adds, are recommended reading for his creative writing students at the university.

“Morrison made me realise how important our stories are as communities and makes no effort trying to write for other people.

“She says she writes for black people and that made me bold enough to say, ‘Well I write in Setswana.’ Therefore, I am writing first and foremost to South Africans before I can even attempt to want to be admired outside South Africa.” Mokae says.

He highlighted possible solutions for preserving home languages, emphasising that, without use, languages die.

Like Seletisa, he expressed concern that South Africa isn’t doing enough to promote languages, noting the predominance of English and Afrikaans in libraries and bookstores.

He suggests publishers make books in home languages more accessible, with government investment in purchasing them for libraries.

“I am certain that when you go to a bookstore in Kimberly and you look for Setswana books — an area where the language is widely spoken — it’s highly likely you’re going to find a few Setswana titles.”

Regarding educational, corporate and government institutions, Mokae says: “When you see language as a body of knowledge and you realise how many bodies of knowledge are being disregarded and undermined, it’s actually disheartening.”

He also says government funding for translations, as suggested by Kenyan author Ngugi wa Thiong’o, could help decolonise stories dominated by the English language.

“This will actually not solve the whole problem, but this will at least repatriate stories that are colonised by the English language and repatriate them to their linguistic homes where they belong,” Mokae says.

In the recent past, there has been a steadily growing generation of writers moving to translating and writing in their mother tongue. To mention a few: Tuelo Gabonewe, with two Setswana erotica novels; Nakanjani Sibiya, who pens short story collections in IsiZulu, and also Khalirendwe Nekhavhambe who writes in Tshivenda. Yamkela Khoza Tywakadi, Lorato Trok and Cape Town-based Dr Xolisa Guzula are some trailblazers in the South African translation space.

Seletisa and Mokae are certainly a firm part of these unyielding cultural activists advocating for linguistic preservation and pride in South Africa through the written and spoken word.

The quiet power of Moses Seletisa’s Sepedi poetry and Sabata Mokae’s Setswana novels