Free-living amoebas, which are single-celled organisms that do not require a host to live, pose a dangerous threat to humans. They are prevalent in both natural water sources and drinking water systems. They are also notoriously difficult to kill and can harbor other pathogens. More research needs to be done to effectively control amoebic disease spread.

A Trojan horse

Amoebas’ “widespread presence in both natural and engineered environments poses significant exposure risks through contaminated water sources, recreational water activities and drinking water systems,” said a paper published in the journal Biocontaminant. While most species are harmless, there is a subset that can have serious public health consequences, like Naegleria fowleri, the brain-eating amoeba.

The brain-eating amoeba is not the only one to be worried about. Others can “cause painful eye infections, particularly in contact lens users, skin lesions in people with weakened immune systems and rare but serious systemic infections affecting organs such as the lungs, liver and kidneys,” Manal Mohammed, a senior lecturer of medical microbiology at the University of Westminster, said at The Conversation. The level of human exposure to amoebas is “likely substantially underestimated,” said the study, as “amoebic infections are prone to clinical misdiagnosis as other diseases.”

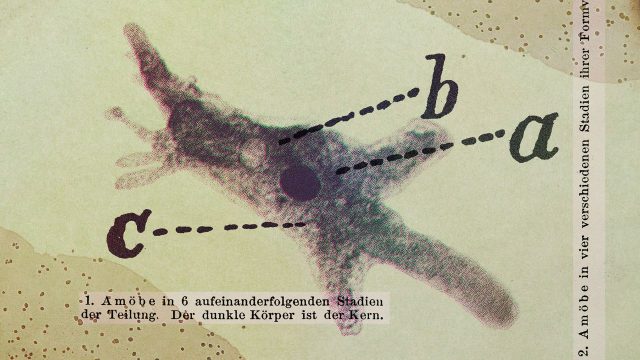

Free-living amoebas have the “ability to change shape and move using temporary arm-like extensions called pseudopodia,” or “false feet,” Mohammed said. This allows them to thrive in even the most inhospitable of environments, including extremely high temperatures and in the presence of strong cleaning chemicals like chlorine. Along with their resilience, amoebas “act as hidden carriers for other harmful microbes,” said a release about the paper. “By sheltering bacteria and viruses inside their cells, amoebae can protect these pathogens from disinfection and help them persist and spread in drinking water systems.” This is known as the Trojan horse effect, and it can contribute to the prevalence of antibiotic resistance.

Deep water

Unfortunately, “most water systems are not routinely checked for free-living amoebas,” said Mohammed. Since they can be rare, and may “hide in biofilms or sediments,” they “require specialized tests to detect, making routine monitoring expensive and technically challenging.” Generally, water testing “relies on proper chlorination, maintaining disinfectant levels and flushing systems regularly,” which can help but does not guarantee the removal of amoeba. There is a lack of knowledge on how to deal with amoebas, making it “challenging to establish science-based regulatory standards for water treatment that are guaranteed to be effective against all threatening species,” said the study.

The problem is also likely to worsen because of climate change. The rising temperatures are “expanding the geographic range of heat-loving amoebae into regions where they were previously rare,” said the release. Mitigating the spread “requires comprehensive strategies combining enhanced surveillance, rapid diagnostics and targeted environmental interventions,” said the study. There should also be more public awareness about the risk of amoebic infections, especially in natural bodies of water.

“Amoebae are not just a medical issue or an environmental issue,” Longfei Shu, the author of the study, said in the release. “They sit at the intersection of both, and addressing them requires integrated solutions that protect public health at its source.”

Small and very mighty