For nine years Dwight Pile-Gray was proud to be a guardsman, one of the soldiers who march at Trooping the Colour. Then a junior colleague’s derogatory attitude exposed a culture of racism in the army. Now he is speaking out

A report by Janice Turner for The London Times.

In July 2021, Lance Sergeant Dwight Pile-Gray had a medical appointment at Wellington Barracks in London where he had been based for nine years. It was from here, as a French horn player with the band of the Grenadier Guards, he had marched many times to nearby Buckingham Palace for Changing the Guard, to Horse Guards Parade for Trooping the Colour or, the event he most cherished, Remembrance Day at the Cenotaph.

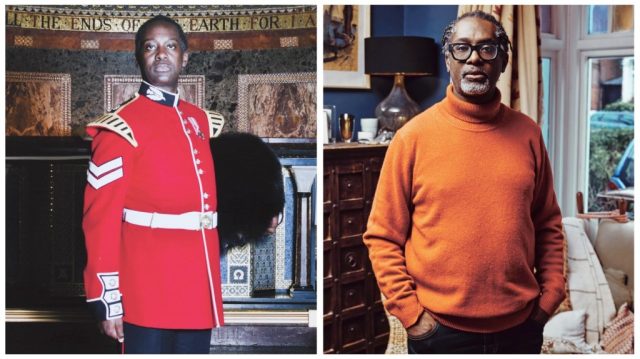

Among the musicians in the red, gold-buttoned tunics of his regiment — known as “the first and finest” — Pile-Gray, now 55, was distinctive in one regard: he was a rare black face and the first Rastafarian in the British Army to keep his traditional locks, worn piled up in a bun inside his bearskin helmet — “a trick I learnt from the female soldiers”.

But that morning, seeing a doctor about an eye infection, he was in smart civvies: a paisley shirt, shorts and aviator sunglasses. After his appointment, he left the barracks briefly to call his wife, Anna, and only turning back did he realise he had left his security pass in his locker. The protocol when a soldier forgets his ID is to send him into the guardroom where someone will vouch for him. If this had happened, Pile-Gray would still be in the army.

Approaching the gate he said to the guard, “Sorry, mate. I’ve left my ID inside.” The guard — half his age and, as a lance corporal, below him in rank — replied with a sarcastic, “Oh, really?” Pile-Gray gave his name and position. “This gentleman,” sneered the guard, “thinks he’s left his ID in here. Does anyone know him?” Bristling at his condescension, Pile-Gray repeated his details curtly. “I don’t need your attitude,” replied the guard. After this, Pile-Gray, now furious, told the lance corporal to “put your f***ing feet together [stand to attention] when you talk to me”.

Once inside, Pile-Gray changed into his uniform and returned to the guardroom. “I knew he had a job to do, but I wanted to explain the way he spoke to me was wrong,” he says. On seeing him approach, the lance corporal said, “Oh, am I going to get a bollocking?” and summoned his staff sergeant as a witness. Pile-Gray explained that, since he had been in civvies and the guard hadn’t recognised him, he should initially have been addressed as “Sir”. “I said that if I’d been a 53-year-old white man, I would have been treated differently.” At this the staff sergeant said, “If you’re going to play the race card, I’m not going to speak to you,” and walked away.

With the Scots Guards, 2015. “The army’s about being the right fit. I’m not sure black soldiers are ever the right fit”

Pile-Gray, with a 15-year unblemished army record, who had never once made a complaint about the racism he experienced, was livid. An angry but not physical exchange followed in which he swore at the staff sergeant. Afterwards he went straight to the garrison commander, a lieutenant colonel, to apologise and explain the circumstances. The lieutenant colonel asked if he wanted to make an official complaint, but Pile-Gray said no, he preferred mediation, “To sit down with the two men, out of uniform, and let them understand why I felt humiliated by their disbelief I could be a soldier.”

The garrison commander thought this an excellent plan. Pile-Gray left, but the lieutenant colonel followed him downstairs. “He wanted to ask me if there was still racism in the army. I said, ‘Of course there is.’ He said, ‘I thought we’d got rid of all that.’ Then he asked what would happen to his mixed-race nephew, who was joining the Coldstream Guards. I said, ‘He’ll get abuse, sir.’ ”

DWIGHT PILE-GRAY WAS BORN IN CROYDON, SOUTH LONDON, to parents who had arrived from Guyana in the late Fifties. His mother, Sheila, was a nursing sister who went to university and retrained as a teacher. His father, John, worked as a civil servant and legal adviser, but his true passion was classical music. Every Sunday the house resounded with Beethoven, Tchaikovsky, Schubert and Bach, the St Matthew Passion at Easter. “No pop music was allowed.” A draconian man, John insisted his four children sang in the church choir and learnt the piano, then allotted each a second instrument. “My sister played the violin, my middle brother the clarinet, my older brother the trombone. I was given the French horn.” His siblings just tolerated their instruments; Pile-Gray fell in love. “I always say the horn chose me.”

After playing with youth orchestras and passing his grade 8 exam at 17, he applied for music college. But just weeks before his 18th birthday, his mother died unexpectedly of a heart condition. “It was devastating,” he says. “I flunked everything. My A-levels. My auditions.” Then, only six months after Sheila’s death, John remarried and kicked all his children out of the family home to make way for his new wife and stepchildren.

Pile-Gray moved in with his older brother, abandoned hope of a music career and sold his French horn. He also became a Rastafarian, a spiritual path that requires followers to abstain from eating meat or drinking alcohol and men not to shave and to wear their hair in “locks”.

He retook his A-levels and for the next decade, Pile-Gray had bank and insurance jobs, before finding well-paid and enjoyable work at IBM. Moving to Birmingham, he managed IT teams that worked for the NHS, businesses and councils, a job that involved a lot of driving. He started tuning into Classic FM. “I’d think, ‘I’ve played that piece, and that.’ ” It reawakened his childhood love for classical music. “I was almost 30 and getting to a crossroads,” he says. “I thought, ‘OK, I need to go to university.’ But what should I do? Computer science? That’s kind of boring. I knew if I didn’t try for music college now, I never would and I’d always regret it.”

Playing the French horn in 2017

So he quit his job, bought a horn and found a teacher in Pete Dyson, a player with the Birmingham Symphony Orchestra. “He said, ‘I only teach conservatoire students. So we’ll have one lesson. If you’re any good, I’ll teach you.’ At the end, Pete said, ‘You’re really good. I’m going to teach you.’ He was an amazing player and all-round top guy.” After two years, Pile-Gray then 32, was accepted to study at Trinity College of Music in London.

Although he loved his course, he quickly realised that not playing for a decade put him at a serious disadvantage against 18-year-olds who had studied the horn continuously for years. “I knew I would never be good enough to play in the London Symphony Orchestra or the Philharmonia,” he says. “That was hard.” Yet having rediscovered his passion, he funded himself through a postgraduate diploma at Trinity with part-time jobs. This course ran mentorship schemes, including one with the Royal Artillery band in Woolwich. “They said, ‘Look, you can come in any time you want.’ I played in some gigs with them. It was all really good.”

Pile-Gray saw a route to being a professional musician by signing up to the army for four years. His father had medals from his military service and, as a boy, Pile-Gray had considered joining the Royal Corps of Signals. But he was now almost 37, the army’s upper age limit and had to persuade the recruitment officer to bend the rules. “I said, ‘Look I’m a horn player. I’m a graduate. The army needs horn players, so let’s start the process, and if it doesn’t work then at least we’ve tried.’ He burst out laughing and said, ‘OK.’ ”

Filling in his army forms, Pile-Gray realised Rastafarianism was not listed as a religion and was told he would need to cut his hair. But finding an online MoD document that did recognise his faith, he asked permission to keep his locks. The matter went up the army hierarchy until he was interviewed by a colonel who asked what being a Rasta entailed. Did it mean he smoked drugs? He explained it was not compulsory and he did not. Did he know his beard would break the seal on a chemical weapons mask? He promised to shave if war broke out. He had to send in photographs and finally his hair was approved if, like female recruits, he tied it back.

At basic training Pile-Gray was twice the age of other recruits. “I was quite fit, or thought I was, but it was hard. I didn’t care though, because it was a means to do what I wanted — play music.” Afterwards he was sent to the Royal Military School of Music, then in Kneller Hall in Twickenham, to learn his trade. Marching while playing an instrument requires discipline and, for brass and wind musicians, great stamina. “You must be in line with the person in front of you and those at the side. You need to watch what the drum major is doing with his mace. You’re jogging along while blowing into your instrument, staring at little dots on cards you need to change.”

New recruits shared barracks and there was much laughter as they struggled to learn the complex drills. Although the sole black face at that time, he experienced no racism from colleagues. Then the course ended and postings were announced.“One guy wasn’t even a horn player,” says Pile-Gray. “He’d just retrained from the cornet, but he was sent straight to a London regiment.” Although a music graduate, Pile-Gray was assigned to the less prestigious Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers (REME), then based near Reading.

When he joined the Guards, he asked permission to keep his locks and promised to shave if war broke out

His disappointment quickly lifted. Billeted together in isolated barracks with their own bar, and taking long coach journeys to concerts, the band bonded closely. “As the first visible Rasta in the army, I felt slightly protected by my colleagues. The first day I asked the colour sergeant where I should sit and he said, ‘Next to me,’ which I did from then on. And, honestly, he made me laugh so much. We had a brilliant time.” One night, playing in a quintet for an officers’ dinner dance, no vegetarian food was laid on. “The host said to me, ‘Haven’t you got enough celery?’ And the quintet leader kicked off. He said, ‘How dare you. Why is there no proper food for him?’ ”

Besides the camaraderie, Pile-Gray loved the rigour and order of army life. “I preferred an environment where I knew what was expected of me, what time to start. I had a really great time.” In his six years with REME, he played in Canada, the US, Germany, Holland, France and in front of 25,000 people in Red Square in Moscow. In 2010, he applied for the bandmaster’s course, which could accelerate his promotion, perhaps to a director of music. He was rejected, but told to reapply once he had deeper knowledge of the army and experience as a conductor.

So he studied part-time for a master’s degree in conducting at the London College of Music and was appointed musical director of a wind band in Chalfont. He also became an army diversity poster boy and appeared on recruitment materials. “Me sitting down pretending to drink, laughing and smiling. The REME guys used to joke about it — ‘There’s Dwight again!’ ”

In 2012, Pile-Gray was posted to the Scots Guards based in Wellington Barracks while living at home in south London. Now he performed at state occasions: receptions for visiting world leaders, the opening of parliament, the Olympic closing ceremony (“Although actually, we were miming there”), the Diamond Jubilee and Baroness Thatcher’s funeral. He loved playing at the Cenotaph on Remembrance Day, “when London is really still, everything’s quiet — as it should be on that occasion — and these old men who can barely walk are marching, not for glory, but for their friends who died. It’s an amazing thing to be part of.”

On his first day at Wellington Barracks he sensed that one of his superiors, friendly to other musicians, had a problem with him. He was advised by a colleague to shave off his beard, “which I did, because you can’t fight every battle”. He also encountered more ordinary squaddies who didn’t know him and he got frequent cries of, “Get your f***ing hair cut,” including once at a big parade in front of senior officers. He was asked constantly where he came from. Pile-Gray either ignored casual racism or responded with a quick comeback.

Pile-Gray taking part in Trooping the Colour

On an army skiing trip, a bandmate was talking about performing on the long march uphill to Windsor Castle. Referring to a cornet player with great stamina, he said, “We used to call him — excuse me, Dwight — n***er lips.” Why did he not call him out? “Because he was one of my training sergeants, a really good guy. Because he wasn’t being malicious and actually, if I’d said something, then he’d have felt crushed. Maybe I should have pulled him aside, as I have done at other times, but I let it go.”

In 2017 he was transferred to the Grenadier Guards and, after acquiring a wealth of army and conducting experience, Pile-Gray reapplied for the bandmasters course. He failed again. This time he was told he had picked up bad conducting habits that could not be rectified in the one-year course. His director of music said he came over as “slightly arrogant” and that, “I have sympathy with the selection panel as they always must ask themselves, ‘Can I see this candidate as a bandmaster in 12 months’ time?’ ” Why, he asked, could they see far less qualified candidates as leaders (including a friend who was amazed Pile-Gray had failed when he had passed), but not him?

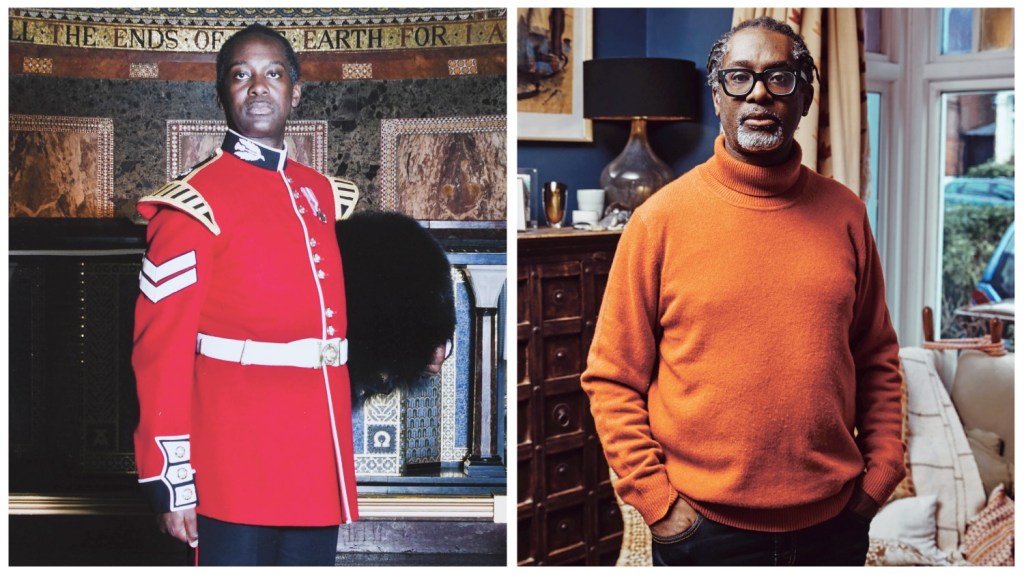

In 12 years, he had risen by only one rank, while musicians who had got on to the bandmasters course in 2010 were now senior officers. He noticed the few other black army musicians were also under-promoted. After this serious knockback, Pile-Gray became deeply disillusioned. He still enjoyed performing with the Grenadier Guards, but his real musical life was increasingly beyond the army. In his spare time he performed with many ensembles including the black Chineke! orchestra at the Proms, conducted and taught music and began a PhD into forgotten black classical composers.

On a research trip to the US, Pile-Gray unearthed a manuscript by Nathaniel Dett, a Canadian-born composer descended from slaves who merged Negro spirituals with western classical tradition. His piece Magnolia Suite Part 2: No 4 “Mammy” was premiered by the BBC Philharmonic on Radio 3 last year. “My belief is classical music is a western European art form,” he says. “So of course the canon contains hundreds of white men. Some are very good; some are not. My belief is, forget the mediocre and add in the best black and female composers, so we have a repository of excellent classical music composed by everybody.”

AFTER HIS MEETING WITH THE GARRISON COMMANDER, Pile-Gray waited for mediation to be set up. But it never was. Instead, he was summoned and charged with insubordination. Moreover, what was at first a minor administrative matter was quickly bumped up to a service offence under the Armed Forces Act. Pile-Gray pleaded guilty because he had never denied losing his temper, was fined a day’s pay and received a blemish on his army record. He was outraged to be treated as a stereotypical “angry black man” while the contemptuous treatment by the staff sergeant and guard who provoked him was never addressed.

Eventually the charity Centre for Military Justice took up his case and he made his own service complaint against the two men. At the hearing, the guard said he now felt “anxious” dealing with Afro-Caribbean people and the garrison commander claimed while other black and minority ethnic soldiers were “super-polite”, Pile-Gray was “highly sensitive” to racial bias and “harbour[ed] injustice”.

The band of the Grenadier Guards at the Drumhead Service in Gheluvelt Park, Worcester

After that, he left the army, rejecting the special party for friends and family he was entitled to as a long-serving soldier. “I felt my whole army career had been a sham and that I’d worked hard, to the best of my ability, all for nothing.”

Feeling the military had literally closed ranks rather than address what he sees as institutional racism, Pile-Gray took the army to an employment tribunal. At the hearing, asked if he was racist, the garrison commander burst into tears. The tribunal noted “a catalogue of missed opportunities by officers in the chain of command right up to the garrison commander, to address and resolve the issues and complaints”. Pile-Gray’s claims of direct race discrimination, racial harassment and victimisation were upheld and this month he was awarded a financial settlement.

For Pile-Gray, who now oversees classical music for children in Islington, lectures in conducting at the London College of Music and is finishing his PhD, this was neither about money nor revenge. (He has chosen not to name any personnel concerned.) It was to improve the lives of soldiers of colour who come after him. He believes the army should create an independent service complaints body, improve its “tick-box” diversity training and, above all, he would like an apology. “In the army, it’s about being the right fit and I’m not sure any black soldiers, even if we have the qualifications, are ever the right fit.” The army music corps in which he invested his talent and energy for almost 16 years, could not imagine him as a leader, while the guard at Wellington Barracks gate could not see him as a soldier at all.

For nine years Dwight Pile-Gray was proud to be a guardsman, one of the soldiers who march at Trooping the Colour. Then a junior colleague’s derogatory attitude exposed a culture of racism in the army. Now he is speaking out A report by Janice Turner for The London Times. In July 2021, Lance Sergeant Dwight