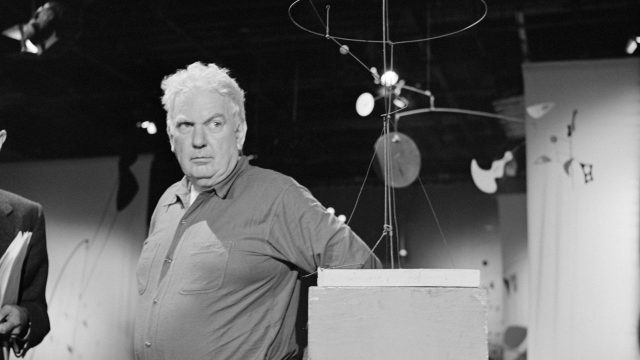

“A master of form, fun, lightness, and surprise,” Alexander Calder is “the one 20th-century artist whom probably no one has ever disliked,” said Willard Spiegelman in The Wall Street Journal. With the opening in September of Calder Gardens in Philadelphia, the American titan of kinetic art (1898–1976) joins the select group of artists worldwide who have museums all their own. Except that in this case, “‘museum’ is the wrong word,” because Calder Gardens is so unique. On an “eccentric spit of land” tucked amid the city’s extensive museum row, the building is mostly hidden below a new public garden, and visitors experience the complex as a “splendid” parade of big and small light-filled spaces that create their own sense of Calder-like movement. With his grandfather’s statue of William Penn in view atop City Hall and his father’s Swann Memorial Fountain a block away, Calder, a Philadelphia native, has been awarded a well-earned homecoming, and his works now on display “have already begun to dance.”

“Calder was long dismissed as a sideshow in American art, a toymaker rather than a prophet,” said Adam Gopnik in The New Yorker. But his approach “reminds us of art’s primary role, which is not to issue statements but to make things: evocative things, funny things, beautiful things, trivial things.” Spending time among Calder’s mobiles and static but equally playful “stabiles,” a viewer “becomes acutely aware of their sheer variety.” One mobile, “a cluster of white leaf shapes strung along long horizontal arcs,” has “the aloof grace of an albino peacock.” Another “evokes a mechanized Japanese cherry tree.” To display these wonders, as well as complementary works by Calder’s father and grandfather, the architectural firm Herzog & de Meuron designed a “deliberately ‘irrational’ exhibition space” whose main visible wall is sheathed in reflective steel, “mirroring the gardens around it rather than asserting its own profile.”

It’s surely “one of the strangest cultural complexes to be built anywhere in recent years,” said Oliver Wainwright in The Guardian. “Part barn, part cave, and part rolling meadow,” this “beguiling” new attraction compresses “a whole universe of gallery types into one compact encounter.” After crossing busy Benjamin Franklin Parkway, visitors climb a hill planted by Piet Oudolf, who’s known for his work on New York City’s High Line. The plantings, unfortunately, are years from maturity, but it’s still remarkable to come upon openings in the earth that offer the first glimpses of Calder’s colorful sculpture. Because the artist himself despised art-world formalities such as nameplates and explanatory texts, I completed the journey beyond “feeling entertained but none the wiser about Calder.” Maybe that’s fine. “Theories may be all very well for the artist himself,” he once said, “but they shouldn’t be broadcast to other people.”

A permanent new museum