An obituary by Clay Risen for The New York Times.

He was the voice of the Young Lords in the 1970s, pushing to improve life in poor New York neighborhoods. Later, he won Emmys as a local media celebrity.

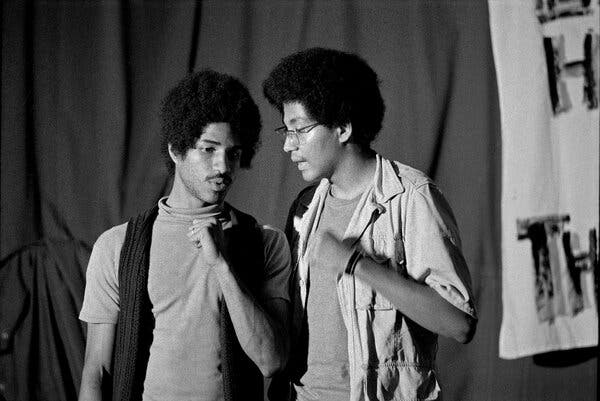

Pablo Guzmán, who gained widespread media attention in the early 1970s as a leader of the Young Lords, a Puerto Rican activist group based in East Harlem, then flipped the script to become an Emmy-winning television news reporter, died on Sunday in Westchester County, N.Y. He was 73.

His wife, Debbie Guzmán, said the cause of his death, in a hospital, was cardiac arrest.

The Young Lords, which Mr. Guzmán helped found in 1969, grabbed New York’s attention with high-profile street actions intended to highlight the deplorable condition of neighborhoods like the South Bronx and East Harlem.

They built walls of garbage across city streets to protest ineffective sanitation, then set them on fire; they took over a church and used it to offer free breakfast to school children; and they briefly occupied a Bronx hospital, turning it into a free clinic.

Sanford Garelik, the City Council president at the time, derided the Young Lords as “terrorists.” Both the F.B.I. and the New York Police Department spied on the group.

He developed close relationships with reporters, giving them a heads-up before the next Young Lords action. He gave news conferences full of wit and quotable quips. And he was a wizard on the stump, drawing on influences like Malcolm X and Huey P. Newton to give voice to Puerto Rican identity at a time when the community was either ignored or feared by the city’s white establishment.

“If the Young Lords were considered the darling of the New York press, it was because of how Pablo organized the narrative,” Mickey Melendez, another founding member of the Young Lords, said in a phone interview. “We were good copy.”

Like many street-level organizations of the late 1960s and early ’70s, the Young Lords were short-lived. Undermined by law enforcement and torn by ideological differences, they folded by 1975, but not before leaving an indelible mark on the city.

Not only did their activism force the city to act — improving garbage pickup, banning lead paint in homes and building a new hospital in the Bronx — but they also brought pride and awareness to New York’s Puerto Rican community. They helped drive the Nuyorican renaissance of the 1960s and ’70s and gave legitimacy to the wave of Puerto Ricans who poured into the city’s political and cultural establishment over the next decades.

“The Young Lords gave Puerto Ricans a kind of coming-out party in the city,” said Johanna Fernández, an associate professor of history at Baruch College and the author of “The Young Lords: A Radical History” (2019).

Mr. Guzmán took his media skills and street credibility to his next career, in journalism. He started out writing freelance articles for The Village Voice and hosting and producing a series of radio shows before becoming a reporter for WNEW-TV, a Fox affiliate.

He went on to report for WNBC-TV and, from 1996 to 2013, for WCBS-TV as a senior correspondent. He won two Emmys, including one for his coverage of the murder of a New York police officer.

In these roles Mr. Guzmán became a celebrity of a different kind, for a different generation of New Yorkers. Avuncular, witty and erudite, he was at home interviewing children and mobsters, sanitation men and diplomats.

He was the mob boss John Gotti’s favorite reporter, the one Mr. Gotti called immediately after emerging from court during his trials of the 1980s and ’90s.

“People found him approachable,” Geraldo Rivera, who was a lawyer for the Young Lords before becoming a TV reporter, said in a phone interview. “He could go where a lot of rookie journalists couldn’t go.”

Paul Guzmán was born in Manhattan on Aug. 17, 1950, to Raúl and Sally (Palomino) Guzmán. His father was a department store manager; his mother was an office worker for Citibank. The family moved to the South Bronx when Paul was young.

He grew up straight and narrow. He was an altar boy at Our Lady of Pity, a Roman Catholic church in the Bronx. He graduated from the elite Bronx High School of Science in 1968, then enrolled at the State University of New York at Old Westbury, on Long Island.

He married Debbie Corley in 1990. In addition to her, he is survived by their children, Daniel and Angela; his mother; and his sister, Tanya Guzmán.

During the second semester of his freshman year, Mr. Guzmán studied at a university in Cuernavaca, Mexico. The experience awakened in him an awareness of his Latino identity: He grew an Afro, began going by Pablo (he later legally changed his name) and returned more interested in street activism than in completing his degree.

“Most of us in the United States did not know what we were,” he wrote in The Village Voice in 1984, describing his generation of Puerto Ricans. “We tended to identify, according to our skin color, with ‘being white’ or ‘being Black.’”

Mr. Guzmán joined a small group of like-minded young activists, mostly Puerto Ricans, to form the Sociedad de Albizu Campos, named for a leading figure in the Puerto Rican independence movement.

Early on, the group read an article about a similar organization in Chicago, the Young Lords, which originated as a street gang in the early 1960s. By the end of that decade, under the influence of the Black Panthers, they had reformed themselves as political agitators.

In 1969, Mr. Guzmán and three others drove to Chicago to meet the Young Lords leadership and returned with permission to start a New York chapter. Less than a year later, though, they split from the Chicago branch, convinced that it was not sufficiently revolutionary.

The Young Lords were militant but not militaristic; despite their stated commitment to “armed struggle,” they rarely carried guns or sought confrontation with the authorities. Instead, Mr. Guzmán encouraged them to stage dramatic actions to embarrass the city into action, like the time they “liberated” — some would say stole — a truck full of equipment used to test for lead poisoning and tuberculosis, both scourges of the city’s poorest neighborhoods.

The group always claimed inspiration from Communist China, and over time their commitment to Maoism deepened. In 1971, Mr. Guzmán joined a delegation of 70 Black and Latino activists on a monthslong trip to China.

But he also reacted to the increasingly sectarian drive among other Young Lords leaders, and to their growing commitment of resources to Puerto Rican independence — efforts, he felt, that eroded their connections to everyday New Yorkers.

After serving nine months in federal prison in Florida for resisting the draft, Mr. Guzmán returned to New York in 1974 to find the organization utterly transformed. Even its name was different — it was now the Puerto Rican Revolutionary Workers Party. He left at the end of the year, and in 1976 the party collapsed.

Thanks to his long career as a journalist, many New Yorkers who recognized him as a daily presence on the nightly news knew little of his time with the Young Lords. And while Mr. Guzmán never hid his history, he preferred to focus on his adventures in front of the camera.

He liked to tell about covering a visit by Nelson Mandela, then the president of South Africa, to New York in the 1990s. At one point a member of the Mandela delegation told him that Mr. Mandela wanted to speak to Mr. Guzmán privately.

“My ego was jumping,” he recounted in an ad for WCBS. “All the other reporters thought I had the inside track. So I went over to him, and he wanted to ask me about John Gotti.”

An obituary by Clay Risen for The New York Times. He was the voice of the Young Lords in the 1970s, pushing to improve life in poor New York neighborhoods. Later, he won Emmys as a local media celebrity. Pablo Guzmán, who gained widespread media attention in the early 1970s as a leader of the