Many in the U.S. are not living long enough to receive Medicare health — especially marginalized communities. The disparity between those who pay into the benefit and those who live to use it is growing and also highlighting the inequality central to the health care system.

Pay to not play

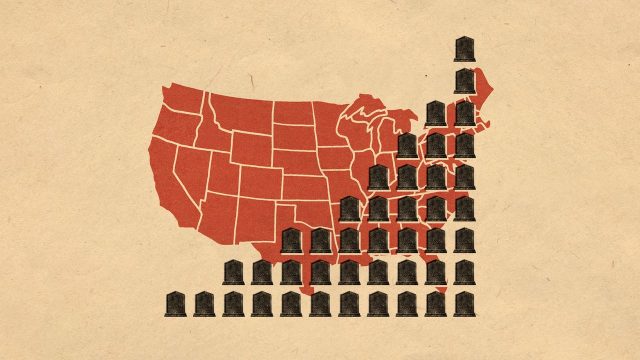

Premature mortality increased in adults aged 18 to 64 by 27.2% between 2012 and 2022, according to a study published in JAMA Health Forum. The increase was 10% higher in Black adults compared to white adults. In addition, “states such as West Virginia, New Mexico and Mississippi had the nation’s highest premature-mortality rates, while Massachusetts and Minnesota fared best,” said The Washington Post.

The new study builds on previous findings regarding life expectancy in the U.S. Between 2009 and 2021, “avoidable mortality increased in all U.S. states, primarily due to increases in preventable deaths, while it decreased in comparable high-income countries,” said a March 2025 study. Then an April 2025 study found that while wealthier people tend to live longer than poorer people in the U.S., even richer Americans have a shorter average life expectancy than those in the top wealth quartiles in comparable European countries.

The findings of the new study also point to a disparity in access to Medicare benefits, which people are only eligible for once they turn 65. “These are people who contribute to Medicare their entire lives yet never live long enough to use it,” Irene Papanicolas, a professor at the Brown University School of Public Health and the lead author of the study, said in a news release. “When you look through the lens of race, it’s clear that one group is increasingly dying before they ever see the benefits of the system they helped fund.” Health care is needed sooner, and many do not have access.

Rigged game

The current Medicare system “effectively bakes structural inequity into a system that was meant to be universal,” Jose Figueroa, a co-author of the study and an associate professor of health policy at Harvard University, said in the news release. “What’s most troubling is that these inequities aren’t shrinking — they’re deepening across nearly every state.”

Black and low-wage workers “disproportionately have jobs that don’t provide health insurance, so they’re either covered by Medicaid, Affordable Care Act marketplace plans or they go without,” said the Post. These groups are more likely to be unable to catch and cure problems before they become deadly. Fixing the system will “require coordinated health and social policy reforms that ensure timely and equitable access to affordable health care coverage before 65 years of age,” said the new study.

Aside from genetics and individual behaviors, “societal factors like breathing polluted air or experiencing chronic — and ultimately corrosive — stress” can also affect how long someone lives, said the Post. “Sustained investments in factors that shape long-term health, such as housing, education and income security” will reduce the amount of premature death, said the study. The “consequences of dying early ripple across generations, causing a loss of productivity not just from the deceased individual but from family members who provide care and support.”

The phenomenon is more pronounced in Black and low-income populations