They are known as the victims of Mexico’s long-running “invisible war”.

Since the then president Felipe Calderón launched his “war on drugs” in 2006, more than 130,000 people have gone missing.

“In many cases, those disappeared have been forcibly recruited into the drug cartels – or murdered for resisting,” said the BBC. But “while drug cartels and organised crime groups are the main perpetrators, security forces are also blamed for deaths and disappearances”.

‘Delirium of necrophilia’

Cases of people reported missing or snatched from the street at gunpoint never to be seen again “were once rare in Mexico”, said The Washington Post. This began to change 15 years ago when huge numbers of disappearances “began to flare into global news, with the discovery of mass graves filled with putrefying bodies”.

By 2023 more than 5,600 mass graves had been recorded in Mexico, said A Dónde van los Desaparecidos. In March this year, a cartel training and extermination camp was discovered on a ranch in the western Mexican state of Jalisco, complete with burned human remains and 200 pairs of shoes.

Strikingly, the discovery – labelled “a human tragedy of enormous proportions” by the UN – was not made by state authorities but by informal search teams of family members known as “buscadores”.

These groups “scour the countryside and the deserts of northern Mexico, following tip-offs, often from the cartels themselves, as to the whereabouts of mass graves”, said the BBC. They carry out searches and campaigning for justice “at great personal risk”, with several themselves disappearing in the aftermath of the Jalisco find.

The “official narrative” is that Mexico’s violence is “entirely the fault of drug cartels, period”, said author Belén Fernández on Al Jazeera. “This rationalisation conveniently excises from the equation the Mexican state’s established track record of killing and disappearing – not to mention the lengthy history of collaboration between Mexican police and military personnel and cartel operatives.”

This is perhaps why the authorities have been hesitant to acknowledge the scope and scale of the crisis, with former Mexican president Andrés Manuel López Obrador even going as far as to accuse Mexicans involved in the search for the missing of a “delirium of necrophilia”. According to Mexico’s National Register of Missing and Disappeared Persons, for a year while Obrador was in office, between May 2022 and May 2023, an average of 27.6 people went missing per day, or more than one person per hour.

Amnesty International now estimates the rate of disappearances stands at 30 per day.

‘Systematic and widespread’

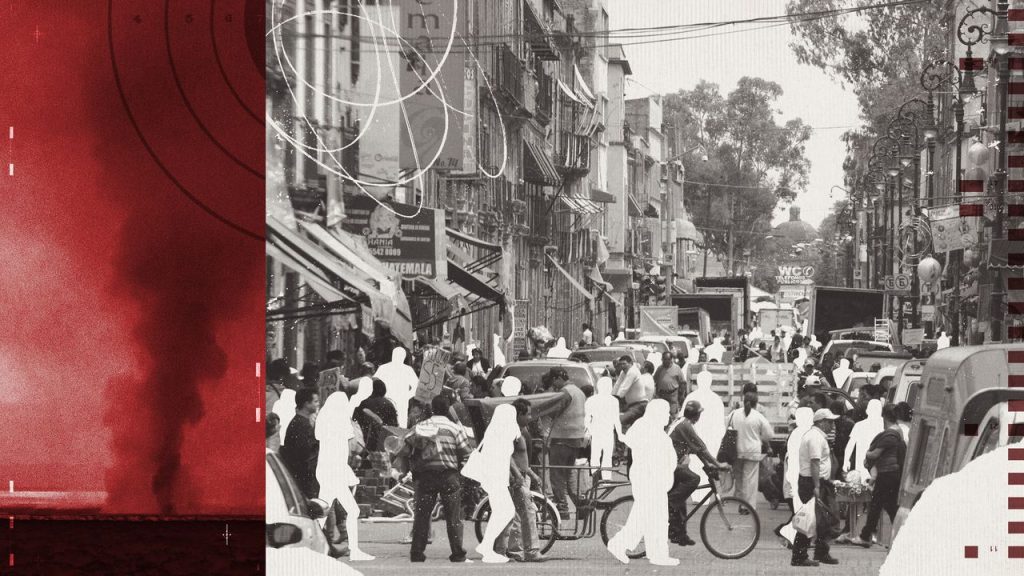

Last month, thousands of people took to the streets across Mexico in protest at the lack of action on the issue by officials.

“The wide spread of cities, states and municipalities where demonstrations were held illustrated the extent to which the problem of forced disappearances affects communities and families across Mexico,” said the BBC.

For the first time, the UN Committee on Enforced Disappearances has opened a procedure for the case of Mexico. For the committee’s experts, who have been studying the case for a decade, there are indications of a “systematic and widespread” practice, said openDemocracy.

“As has pretty much been par for the course with all ostensible global anti-narcotic endeavours orchestrated by the US, the Mexican drug war did nothing to curb international drug traffic but much to render the country’s landscape ever more blood-soaked,” said Fernández.

That has not stopped the US government from adopting ever more extreme measures. It has already labelled six Mexican cartels terrorist groups and now the Trump administration is weighing possible military action against them.

“But Mexican cartels aren’t dependent on a handful of high-profile extremists,” said The Washington Post. “They’re among the country’s top employers and often have relationships with local politicians and police. Disappearances are a sign of their hidden control. Killing or capturing a few leaders is unlikely to destroy their structures.”

“As Mexico’s invisible war rages on, disappearance may have already become normalised,” said Fernández.

130,000 people missing as 20-year war on drugs leaves ‘the country’s landscape ever more blood-soaked’