Free speech is a bulwark of open societies, because it allows ideas and information to be shared, authority to be questioned, and abuses of power exposed. In “On Liberty” (1859), John Stuart Mill gave these ideas their most influential expression. But freedom of speech has long had its critics, even in liberal societies, and the US scholar Stanley Fish argued that, because there are so many exceptions, it doesn’t really exist as a principle. But though imperfect, free speech is still by most measures better than the alternative: speech more closely regulated by government.

How old is the idea of free speech?

It’s relatively modern. For most of human history, it was regarded as self-evident that words can have dangerous consequences. In his recent book “What Is Free Speech?”, the historian Fara Dabhoiwala notes that the saying “Sticks and stones may break my bones, but words will never hurt me” dates only from the 19th century, but the Book of Ecclesiasticus states: “the stroke of the tongue breaketh the bones”.

An English law of 1275 made it a crime to “tell or publish any false news or tales”, while blasphemy, heresy, defamation and “scolding” were crimes punished, often severely, in medieval and early modern Britain. This only began to change during the Civil War, when the emergence of new sects made a limited degree of religious toleration a necessity.

How did things change?

Broad, secular free speech as we know it now dates from the 1720s, when it was formulated in “Cato’s Letters”, published in London pseudonymously by two journalists, Thomas Gordon and John Trenchard. “Without Freedom of Thought,” they wrote, “there can be no such Thing as Wisdom; and no such Thing as public Liberty, without Freedom of Speech: which is the Right of every man, as far by it, he does not hurt or control the Right of another.”

This principle, very radical at the time, spread across Europe, influencing in particular the philosophes of the French Enlightenment. In Europe, the idea of a right to free speech took root, though usually in a qualified form. The Declaration of the Rights of Man, published in 1789, stated that it must be balanced with responsibilities, and abuses of free speech should be punished by law.

In the young United States, however, where “Cato’s Letters” were particularly influential, the First Amendment of 1791 took an “absolutist” position: Congress should make no law abridging freedom of religion, speech or assembly. This led to a gap between the US and Europe that is clearly visible in the debate today.

What about in Britain?

Freedom of speech in Parliament was guaranteed under the 1689 Bill of Rights. Although it became an article of political faith, and a crucial thread in the common law, there were no broad constitutional guarantees of free speech for the public, until the European Convention on Human Rights was embedded directly in UK law by the Human Rights Act 1998. Article 10 of the ECHR guarantees “the right to freedom of expression”, subject to “restrictions or penalties”.

In Britain, the main exceptions are: incitement to crime and hatred; threats and harassment; defamation and slander; terrorism and threats to national security; fraud; obscenity and child pornography; and contempt of court. In practice, many other exceptions exist. In the US, by contrast, restrictions are more tightly drawn. Incitement is only a crime if it leads to “imminent lawless action”. Offensive or hateful speech is mostly protected. Defamation is hard to prove in court.

What is the concern in the UK now?

Much of it relates to online publishing: social media has made it much easier for members of the public to break the law. Lucy Connolly was convicted for inciting racial hatred in 2024, because she tweeted after the Southport killings that people should set fire to hotels housing asylum seekers. Both the conviction itself, and the length of the sentence (two years seven months) have been much debated.

This month, the comedy writer Graham Linehan was arrested by armed police at Heathrow because of tweets in which he recommended punching trans women who went into female-only changing rooms “in the balls”. But such cases are the tip of the iceberg.

What other concerns are there?

The 2003 Communications Act made it illegal to send “grossly offensive” or indecent communications, or “persistently” to use a communications network to cause “annoyance, inconvenience or needless anxiety”. There were more than 12,000 arrests in England and Wales under the Act and related laws in 2023.

The new Online Safety Act has also been criticised. It creates a series of new offences, some of which, such as sending unwanted sexual images, are uncontentious; others, such as sending a “false” communication with the intent of causing “non-trivial harm”, look potentially problematic. By early 2025, 292 people had been charged under the Act. In addition, police forces now also log “non-crime hate incidents” – where some perceived hostility to a vulnerable group is expressed, which falls short of a hate crime.

Is this just an online problem?

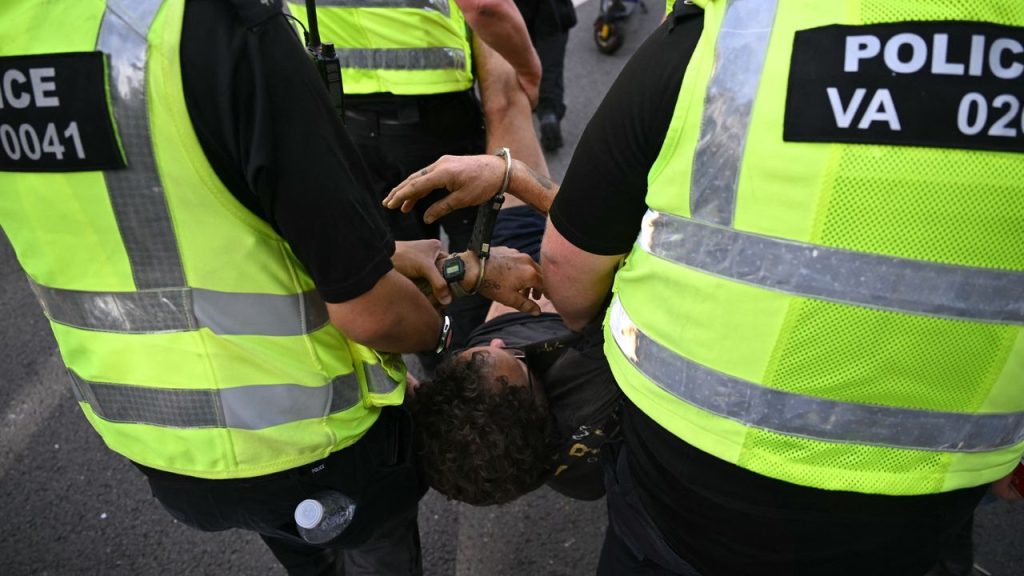

No. Free speech covers so many areas of life that the list of potential threats is long, from the “cancel culture” allegedly prevailing in some universities to the Public Order Act 2023 – which imposed extensive bans and controls on certain forms of protest. The proscription of the Palestine Action group has led to hundreds of people being arrested merely for expressing support for it. J.D. Vance, the US VP, has criticised prosecutions of the Christian protesters who have violated “safe access zones” around abortion centres – which prevent protesters not only harassing visitors but also, it seems, silently praying.

What should be done?

The argument around free speech is highly polarised, with advocates often supporting the kinds of free speech that they prefer: Nigel Farage is a supporter of Lucy Connolly, but has called for crackdowns on pro-Palestine protesters. Donald Trump lionises free speech, but is suing The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal for $15 billion and $10 billion respectively. Nevertheless, a consensus is building that there are too many vague speech offences on the UK statute books, particularly as regards online activity. The Health Secretary, Wes Streeting, recently said that the government agreed that the laws needed to be looked at anew, to ensure police actions reflect the “priorities of the public”.

The Trump administration thinks that free speech is in retreat in Britain. What do we mean by freedom of speech, and is it in danger?