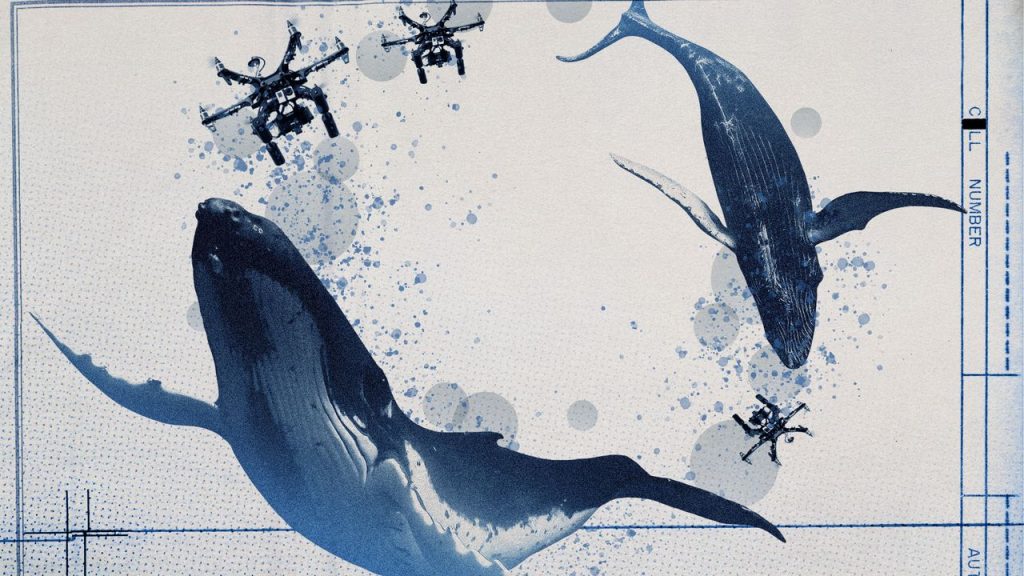

Arctic marine life is notoriously difficult to study because of its remoteness. But drones have enabled whales to be monitored and diagnosed while being minimally invasive, according to a new study.

Arctic air

By having drones collect samples of whale breath or “blow” from humpback, sperm and fin whales in the northeast Atlantic to screen for pathogens, researchers have “confirmed for the first time that a potentially deadly whale virus” is “circulating above the Arctic Circle,” said a news release about the study published in the journal BMC Veterinary Research. Cetacean morbillivirus can cause “immunosuppression and severe disease in cetaceans,” said NPR. The disease has previously caused “several mass die-offs” of whales, dolphins and porpoises.

When whales come to the surface of the ocean to breathe, they “release a plume of air mixed with microscopic droplets from their blowholes,” said Discover. The droplets “carry traces of cells, microbes and viruses from the animals’ respiratory systems.”

To collect them, researchers “hovered the drone over a whale that looked like it was about to blow” and then “captured the exhales on petri dishes” attached to it, said NPR. The droplets were then screened to find pathogens similar to how diseases are identified in humans.

Virus vigilance

Species in these regions are difficult to monitor. Usually, collecting samples from wild whales requires “getting close to them in a boat and then shooting a dart gun to snag a small skin sample,” said NPR. And most collected samples are from dead whales.

“Drone blow sampling is a game changer,” Terry Dawson, a professor at King’s College in London and a co-author of the study, said in the release. It “allows us to monitor pathogens in live whales without stress or harm, providing critical insights into diseases in rapidly changing Arctic ecosystems.”

“Dense winter feeding aggregations, where whales, seabirds and humans interact closely, could increase the risk of viral transmission,” said Oceanographic. Drone surveillance can also identify deadly threats to other marine life before they spread.

The “priority is to continue using these methods for long-term surveillance, so we can understand how multiple emerging stressors will shape whale health in the coming years.” Helena Costa, the lead author of the study, said in the release. While there “aren’t protocols to treat a sick whale,” the animals can still be helped by “reducing their stress during illness by, for example, temporarily altering shipping lanes to avoid them,” said NPR. Or if a whale is “carrying a disease that can spread to humans, governments can limit whale-people interactions.”

Climate change is warming the seas, and Arctic marine life is facing other threats, including “shifting prey,” said Discover. “Expanding shipping routes and growing human presence are altering habitats that many species rely on for feeding and migration.” And infectious disease can “compound those pressures, particularly when animals are stressed or concentrated in smaller areas.”

Monitoring the sea in the air