In 1810, the warrior chief Kamehameha I united the Hawaiian islands into a single kingdom. That same year, said Evgenia Siokos in The Telegraph, he dispatched an extraordinary cargo to the other side of the world, along with a formal appeal to King George III to make Great Britain his own island nation’s “natural ally”. “Should any of the powers which you are at war with molest me,” he wrote, “I shall expect your protection.” The letter was sent with “a gift of astonishing splendour”: a cloak fashioned from “hundreds of thousands of red and yellow bird feathers” – which was worn by only the highest-ranking chief, and which “embodied sacred authority”.

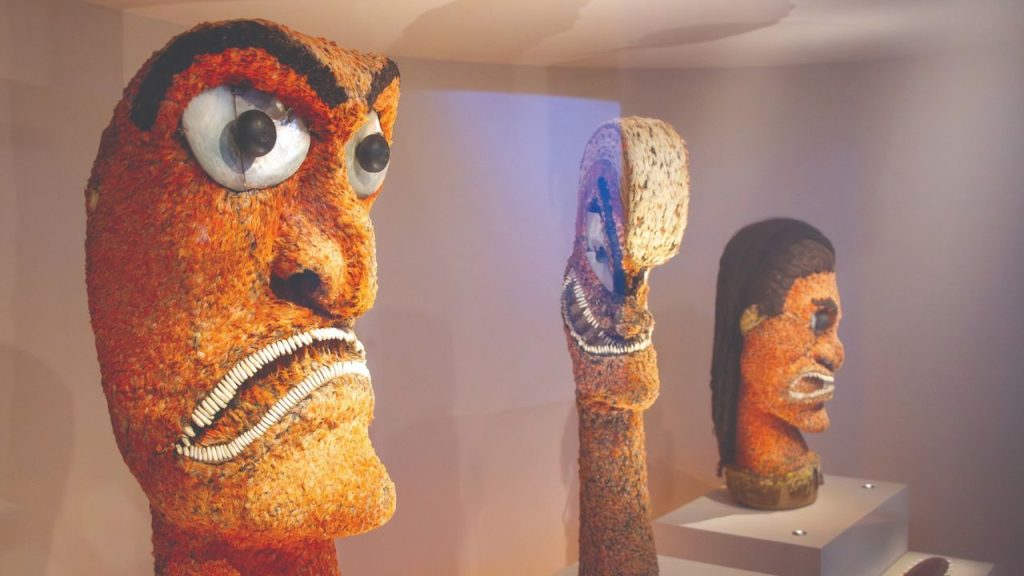

It has not been on public display since 1900, but now takes “pride of place” in a “thrilling” new show that illustrates both the range of the British Museum’s Hawaiian collections, and the friendly relations between the two kingdoms until Hawaii’s official annexation by the US in 1898. There are a wealth of spectacular exhibits, including a trio of feathered akua (gods), which encapsulate a chieftain’s power and “exude a ferocious energy”. The exhibition “treats artefacts as living objects”, and gives voice to a “fascinating, rarely heard culture”.

At the heart of this tremendous show is a “desperate tragedy”, said Laura Cumming in The Observer. In 1824, Kamehameha’s son Liholiho and his wife Queen Kamamalu travelled to London, where they were received with full honours, celebrated by society and slotted in for an audience with the profligate George IV – “one of the worst monarchs in British history”. We see a lithograph of the Hawaiians “beaming” through a performance at the Theatre Royal, and Regency portraits of the couple, dressed in the English fashions of the day. But, unused to foreign climes, they both contracted measles and died within a week of each other; they never met George IV, though he did at least pay their hotel bills, and ordered a ship to transport their bodies home.

The show’s narrative isn’t the easiest to follow, said Laura Freeman in The Times: “I felt somewhat walloped by the history and the who’s who of Hawaiian royal genealogy.” Yet the artefacts it contains are “dazzling”. Highlights include textile panels decorated with “chevrons, stripes, steps and zigzags”; helmets woven from climbing plants; even a “tiny, endearing turtle ornament carved from whale ivory and set with tortoiseshell eyes”. Best of all is a cabinet full of “feathered cloaks, capelets, chokers, tokens, garlands and fans”, many embellished with feathers from the now-extinct o’o bird. It’s a grown-up event that recognises our Georgian ancestors as humans, rather than demons; yet never lets them off “scot-free” for their plundering ways. In short, it’s an exemplary British Museum show – “handsome”, “intelligent” and never less than interesting.

The British Museum, London WC1. Until 25 May.

With some items on display for the first time since 1900, the British Museum’s new show gives voice to a ‘fascinating, rarely heard culture’