Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore, author of Touching the Art (Soft Skull Press, 2023) considers Boom for Real: The Late-Teenage Years of Jean-Michel Basquiat while walking through Baltimore. [Read the full article at Literary Hub.]

Is the point of art to bring us into ourselves, or out? I mean the Parkway theater is my favorite place to go to get out of the heat—I can even stare at the high-concept magenta wallpaper in the bathrooms, digitized popcorn kernels “oating” by. Or notice the shining light outside as it settles over the decaying turn-of-the-century buildings across Charles Street, all those gorgeous reds and browns and look at those plants growing through the cracks in the bricks.

Usually when I go to an old theater I study the details, but with this theater you walk in and you just think: architect. Because the whole place has been gutted, and reimagined. Where did they get all this money?

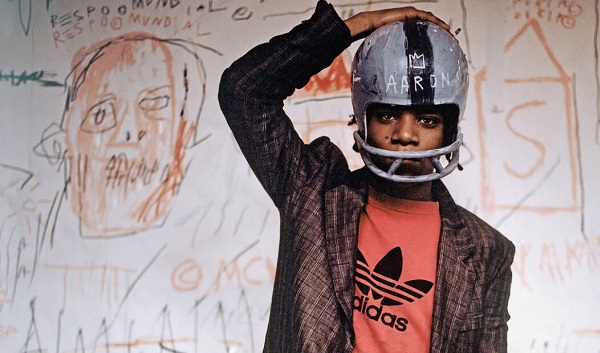

Tonight, I’m watching Boom for Real: The Late-Teenage Years of Jean-Michel Basquiat, which reveals nothing about Basquiat that wasn’t already part of the public record—he was brilliant and wild, charming and manipulative, seductive and ambitious—he was homeless as a teenager, he did a lot of drugs, he became the toast of the art world, he died way too young.

Everyone already knows the myth that Basquiat was a lone genius destroying convention to create his own form. Yes, he was driven to remake himself as a lone visionary in order to become a top-tier art-world commodity, and this actually happened, which is rare for anyone, especially a Black artist, but we already know this killed him, so why portray posthumous canonization as a glorious path? Unless the movie is just about making more money for the ghouls of the art world who have already made millions and millions from Basquiat’s death from an overdose at age twenty-seven.

I’m thinking about the Basquiat show I saw in Seattle in 1994, six years after his death—gazing at those paintings I felt an immediate sensory kinship with the dense layers of self-expression, the wildness, the raw beauty, the way language was interwoven with the visual, became the visual, until it was overcome by it. The movement, the free association that became a method and a system of organization, the disorientation that opens the mind.

The way we can create our own language, the symbols and the strength, the bending, the mesmerizing nurturing scream. I left that show wanting to create, knowing I could create, knowing. In the lobby of the Parkway Theatre there’s a flyer for a new building across from the train station that says:

THE ART OF BALTIMORE

NOW LEASING.

In the photo, it just looks like your average prefab yuppie loft to me, so I’m not sure where the art is, but I guess they mean this neighborhood, designated by the city as an ARTS DISTRICT to change blight into bright lights. The marketing of Baltimore as a creative hub—artists as tools for displacement, a sad story that has obliterated so many neighborhoods over the last several decades, but here it feels more blatant. Maybe because these funded institutions sit in an area so obviously neglected by the city for so long.

Just across the street from the Parkway there are Black people slumped on their stoops in drugged-out immobility due to decades of structural neglect, and next door there’s Motor House, an art gallery/theater/bar complex with a design show called “Undoing the Red Line.”

I walk out of the Parkway, and the graffiti on the street doesn’t look that different than the graffiti in the movie. Is it on display? As if to say: We want what happened in New York in the ’80s to happen here, now. There’s even an alley behind Motor House where graffiti is legal, and all day long there are photo shoots and staged parties promoting multicultural consumption in a segregated city. [. . .]

All the businesses that are never open, but the storefronts still advertise what was there before. The rehab center is the fanciest building on the block—across the street there’s a new art gallery featuring Black artists, in an old brick building.

And I find myself invigorated by the contrasts, the possibility for something surprising to happen—only this is how gentrification works. You look for what you can’t find elsewhere, in neighborhoods where people are having trouble finding anything, and then eventually there isn’t any neighborhood except the one that replaced the neighborhood.

For full article, see https://lithub.com/graffiti-gentrification-mattilda-bernstein-sycamore-on-the-exploitation-of-basquiat/

[Image above: Screenshot, courtesy Magnolia Pictures.]

Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore, author of Touching the Art (Soft Skull Press, 2023) considers Boom for Real: The Late-Teenage Years of Jean-Michel Basquiat while walking through Baltimore. [Read the full article at Literary Hub.] Is the point of art to bring us into ourselves, or out? I mean the Parkway theater is my favorite place to go