Presiding over the fashion empire that bore his name for 50 years, Giorgio Armani, who has died in Italy aged 91, was one of the most influential designers of the late 20th century, said The Times.

At the start of his career, in the 1960s, he had spotted that members of the middle classes had different aspirations from their parents. Members of this post-war generation rejected the stiff conventionality of the past, and yearned instead for comfort, ease and understated luxury.

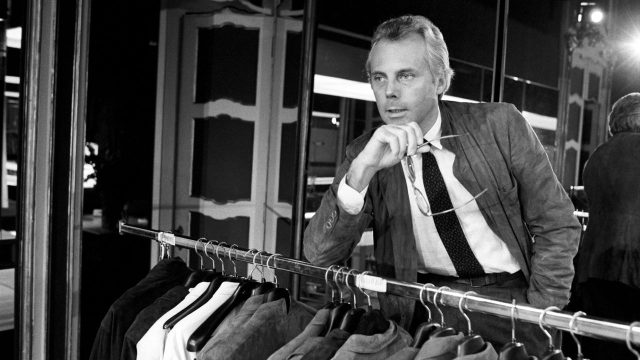

His first great innovation was to deconstruct the traditional tailored suit, by removing canvas linings and thick shoulder pads, lengthening the coat and moving buttons. Armani suits were soft, slouchy and fluid, designed to suit lean, muscular men who didn’t need tailors to disguise the shape of their bodies; he described them as clothes that “give confidence without defining personality”.

Then he turned his attention to the women who were increasingly breaking through glass ceilings in the workplace – creating for them soft, elegant suits, in muted palettes, that would help them project authority without sacrificing their femininity. “I realised that [women] needed a way to dress that was equivalent to that of men,” he said. “Something that would give them dignity in their work life.”

Defining the times

The Armani label prospered in the aspirational, materialist 1980s, aided by some clever marketing. The designer had been quick to see the potential when the sexy clothes he created for the peacocking character played by Richard Gere in the hit film “American Gigolo”, in 1980, caused a sensation, said Vogue. (His suits became even more famous when they were worn by Don Johnson and Philip Michael Thomas on the TV show “Miami Vice”.)

Back then, film stars were not often given outfits by designers; on the red carpet they wore their own, or co-opted the film’s wardrobe department to find them something. But Gere had carried on wearing Armani, and in 1983 Armani opened an office in LA to showcase his wares to Hollywood stylists, said The Guardian.

Being “dressed by Armani” turned out to have a remarkable impact, said The New York Times. Jodie Foster, never known as a fashion plate, entered the best-dressed lists after wearing Armani at the Oscars in 1992. In that decade, the likes of Michelle Pfeiffer and Sharon Stone were repeatedly photographed in Armani gowns, turning the red carpet into a major fashion event, while male stars including Russell Crowe and George Clooney wore Armani tuxedos to exude old-school tinseltown glamour with a modern twist.

Rapid expansion

By then, Armani had nurtured several “brand extensions”, including sunglasses, swimwear and watches. He also opened lower-priced lines such as Armani Jeans, Emporio Armani and Armani Exchange, to run alongside his premium ones, and moved into new markets, notably in Asia. Understanding that what he was selling was not so much clothes as a vision for a lifestyle, he later expanded into homeware, restaurants and hotels, where guests could eat off Armani plates and sleep under Armani sheets.

His extension strategy was risky: other designers undermined their brands by licensing too many products. But Armani – a perfectionist who kept tight control over every aspect of his business – succeeded in maintaining prestige, while selling in vast volume. He said he wanted to make people “look better”, and he wasn’t even troubled when counterfeits emerged. “I am very glad that people can buy Armani, even if it’s a fake,” he once said. “I like the fact that I’m so popular around the world.”

Once the brand had been established, he had shown little interest in setting trends, and for a time critics said that his lines were repetitive, and “out of step”, said The New York Times. Again, he seemed unfazed. The vast advertising budgets deployed by his firm ensured that Armani continued to enjoy “lavish and largely reverent coverage in the press”; and in any case, his classic, determinedly unfussy style would become fashionable again.

Personal complexities

By 2001, Armani became the first designer to have a solo retrospective at the Guggenheim. In the 2000s, he became the first designer to ban models with a body mass index under 18, and the first haute couturier to launch a new collection online.

As his wealth grew, the perma-tanned designer bought multiple houses, and a succession of superyachts, where he entertained A-listers and fashion royalty; but he seemed to live mainly for his work, especially after the death of his long- term romantic and business partner Sergio Galeotti, in 1985, from Aids-related causes. He once said that he sometimes longed for weekends to end, so that he could get back to his offices in Milan, a city he turned into a rival to Paris on the fashion map. In Italy, where he was revered, he was known as “King Giorgio”.

Humble origins

Giorgio Armani was born in Piacenza, in northern Italy, in 1934. He remembered going hungry during the War, and in 1943 he was severely burned when a shell that he and his friends had been playing with exploded; one of them died. “War,” he said, “taught me that not everything is glamorous.” His parents were of modest means, said The Daily Telegraph, but they dressed elegantly and looked wealthy, he said. He shared that sensibility: he loved the cinema, and was fascinated by the look of stars such as Cary Grant, Marlene Dietrich and Humphrey Bogart. He originally planned to become a doctor, but two years into his studies he dropped out. In 1957, he went to work for an upmarket department store in Milan, initially as a window dresser, where he learnt about innovative new textiles and marketing. He had no formal training as a couturier.

In the 1960s, Armani went to work for the Italian designer Nino Cerruti, who asked him to design a menswear collection. This gave him fresh insights into the industry, including how textiles are made. Cerruti, however, rejected the idea that he had discovered Armani. He had, he said, “discovered himself… men like Armani are so rare that, when one emerges, even the blind are aware of it”. In 1970, Galeotti urged him to go freelance, and five years later, they founded Giorgio Armani. “Sergio made me believe in myself,” he told GQ this year. “He made me see the bigger world.” His suits were an immediate hit, and by around 1976, they were being sold at department stores in New York.

As the sole owner of Armani, he built up a fortune estimated at $12 billion. A fiercely private man, and a self-confessed loner, he said he found music distracting, and though he loved art, he had no interest in acquiring art or artefacts, “because you become used to them”, which is a “selfish thing”; his work was his preoccupation and he retained tight control over his empire to the end. “Life,” he said, “is a movie. And my clothes are the costumes.”

‘King Giorgio’ came from humble beginnings to become a titan of the fashion industry and redefine 20th century clothing