The kick-off of the largest art fair in Africa, the Investec Cape Town Art Fair, is this weekend, turning the Mother City into an international art juggernaut for a whole week, with numerous events around the city leading up to it.

One of the most interesting of these will be Exhibition Match, a mash-up of art and football, conceptualised and curated by Alexander Richards and Phokeng Setai, which made its debut in 2022.

Now in its fourth iteration across the Johannesburg and Cape Town art fairs, the project brings together football-related installations, performances and exhibitions, with an actual tournament, played between people from across the art ecosystem.

With Bafana Bafana’s commendable showing at this year’s Afcon, many have been getting nostalgic about our greatest triumph at the tournament — our win in 1996, not long after the country’s first democratic elections.

Captain Neil Tovey’s Bafana team back then is rated by many as the best in recent memory.

The image of Tovey lifting the trophy alongside Nelson Mandela and FW de Klerk is as iconic as Francois Pienaar and Mandela the year before with the Rugby World Cup.

In that photo gallery we can include Mandela and his wife Graça Machel waving at the crowds at the Fifa World Cup, hosted by South Africa in 2010.

The entanglement of football and contemporary South African politics is clear.

Less clear is what art about, or with, football can tell us about our political history and social identity.

The fragmentation of our society during apartheid was mirrored in the segregated football structures of the country but football, as the most democratic and accessible sport in the world, was also instrumental in desegregating sport in the face of apartheid and in its aftermath.

In 1961, Fifa expelled South Africa because of racial discrimination. It was re-admitted in 1963, according to SA History Online, but it was expelled once more after proposing to send an all-white national team to play in the England 1966 World Cup and a black national team to play in Mexico 1970 World Cup. It was readmitted again in July 1992.

During the dark days of apartheid, the sport endured in the great Soweto teams of Pirates and Chiefs and later the powerhouse Mamelodi Sundowns team, which has risen to contemporary prominence and African cup-winning excellence.

The parallels between the art of football, and the ways in which football might illuminate the politics of a society, are not immediately apparent. Football’s populism, its status as perhaps the greatest collective spectacle humankind has to offer, seems counter-intuitive as an art initiative.

Fine art is many things but no one can accuse it of being populist!

The dearth of fine art that has football as a subject bears out the contention that these are separate spheres and experiences.

Yet football has a depth of emotion, the ritual observances of its global fanbase, and the complexity of its narrative as a sporting, a political and a social phenomenon.

All of these are things art can aspire to, say curators Setai and Richards.

“The Exhibition Match project was really born out of a wish to facilitate art that taps into the depth and physical and psychological intensity of football,” says Setai.

Neither curator wishes to see the parallels between football and art too literally. Both are, somewhat idealistically, drawn to their commonality as sharing “spaces for participation”.

Richards makes the point that both activities offer “the potential for free association and play — something that the global organisation of football as a commodity and the commercialisation of art in galleries and fairs re-contextualises”.

Football and art also share the power of provocation. With so much psychological and financial investment in the global game, it translates into a powerful vehicle for political and artistic insight and statement.

Though Exhibition Match has so far treated the potentially powerful impact of football on political art with circumspection, it is something both curators wish to explore further. The format of the project has seen an exhibition or installation related to the Joburg and Cape Town art fairs take place as a precursor to a culminating football match between art-world participants: artists, gallerists, curators, writers and administrators.

In setting up the project this way, the idea of a football/art community comes to the fore. Each year, the selected teams play in match kit designed by high-profile artists, including Robin Rhode and Thenjiwe Nkosi. This year’s match is the fair’s closing event on Sunday.

This more benevolent sense of a football and art community is, particularly in the two most recent iterations of the project, being interrogated by the curators to pressure the ways in which football uncovers political and social tensions, ambiguities and outright hostility.

Football expresses a global sense of commonality, identification with one’s team, joy in victory and despair in defeat. But the dark side of these emotions is also present — misogyny, homophobia, “tribal” violence and nationalist fervour.

At last year’s Joburg Art Fair, Richards and Setai chose to restage a project first conceived more than 20 years ago by Belgium-based South African conceptual artist Kendell Geers. Titled Masked Ball, it invited visitors to kick footballs, covered in the latex masks of various global politicians, against the walls of the venue.

The confluence of the “safe space” of the art fair and the opportunity to kick your least-liked politician in the face proved so much to the liking of visitors, they kicked the balls so hard they damaged the walls.

This performative mix of art and football as politically charged symbolic action is replaced this year by a less interactive, but no less politically insightful, meditation on football violence.

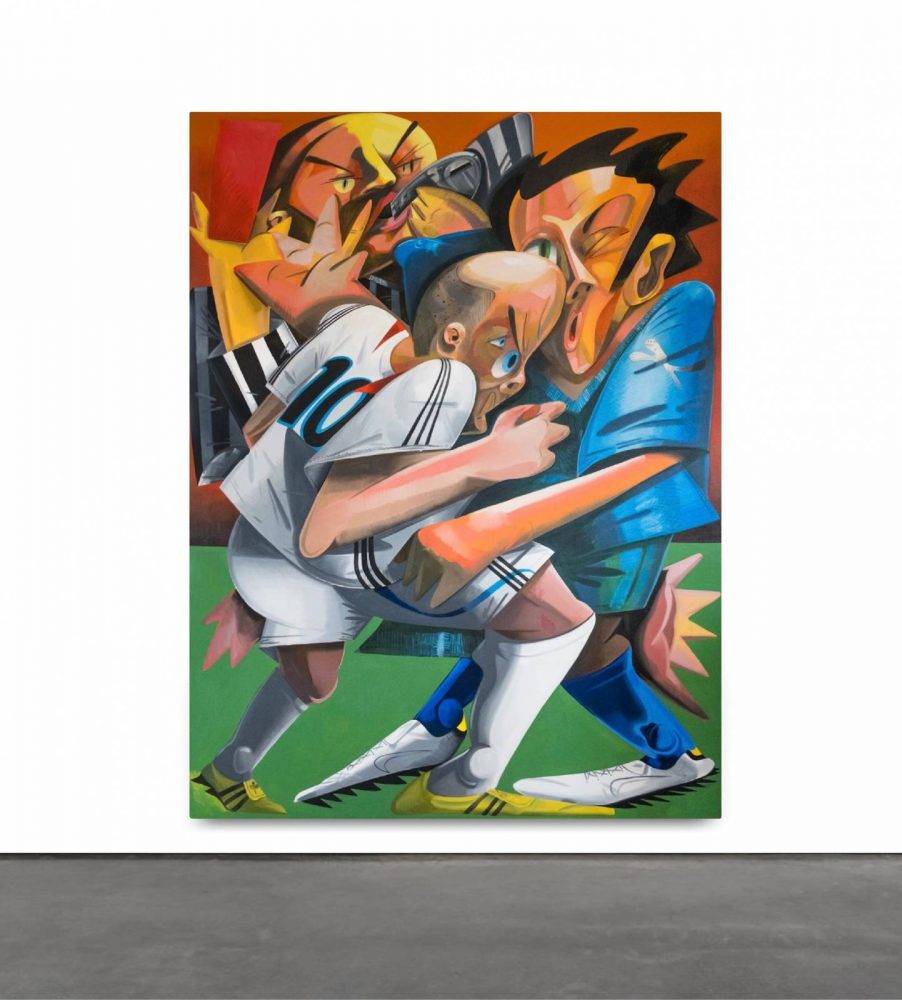

Contemporary artist Callan Grecia brings an exhibition of paintings titled Beef to a solo show outside the main venue at the nearby One Park.

Each work depicts, in Grecia’s bold, graffiti-derived graphic style, a famous on-field conflict between players — hence the slang of the title.

Here is Nigel de Jong executing a drop-kick to the chest of Xabi Alonso in the 2010 World Cup final in Joburg; there is Uruguayan Luis Suarez biting several opponents in high-profile matches. And, presiding over all of them, is French icon Zinedine Zidane’s last significant act as a player on a professional field —headbutting Italy’s Marco Materazzi in the 2006 World Cup Final in Germany, which he had almost single-handedly won for France — and being sent off. He left the field without a backward glance.

Grecia designed the Exhibition Match kit, referencing his family’s history with Durban’s Manning Rangers, one of the only predominantly Indian professional teams in the aftermath of our readmission to international professional football.

Football becomes a vehicle for these community histories, these family memories, in global and shared ways unavailable to other sports. Art has a long way to go.

• Investec Cape Town Art Fair runs from 16 to 18 February at the CTICC, www.investeccapetownartfair.co.za

• Exhibition Match art football match at 4pm on Sunday 18th in Greenpoint. Details at the Art Fair.

• Callan Grecia’s exhibition Beef shows at One Park Cape Town from 15 February.

Project at Cape Town Art Fair demonstrates the links between the sport and art