Marlene L. Daut (Yale University) reviews five essential books for understanding Haitian history. Visit Literary Hub to read the full article and summaries of these important works: Baron de Vastey, The Colonial System Unveiled (2014, Liverpool University Press); Jean Casimir, The Haitians: A Decolonial History (University of North Carolina Press, 2020); Louis Joseph Janvier, Haiti for the Haitians (Liverpool University Press); Yveline Alexis, Haiti Fights Back: The Life and Legacy of Charlemagne Péralte (Rutgers University Press, 2021); and Myriam J.A. Chancy, Framing Silence: Revolutionary Novels by Haitian Women (Rutgers University Press, 1997).

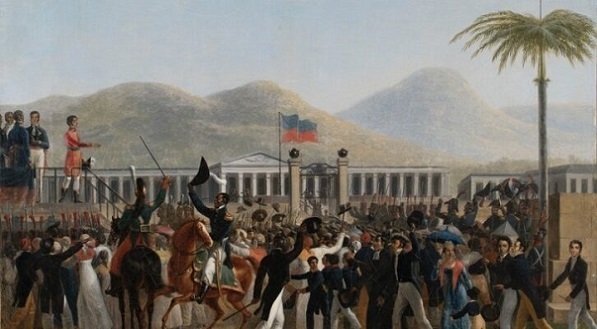

After waging a thirteen-year revolution against slavery in the French colony of Saint-Domingue, the island’s Black freedom fighters declared their independence on January 1, 1804. In the country’s first constitution, issued one year later, the newly renamed Haiti subsequently became the first nation in the modern world to permanently abolish slavery. In a move as equally momentous, in 1807, the Haitian state became the first to declare slavery and the slave trade a “crime against humanity.” Yet even though Haitians ended slavery more than three decades before Great Britain, more than four decades before France, and more than six decades before the United States, Haiti is often left out of the story of how the world went from slavery to freedom.

The Haitian anthropologist and historian Michel-Rolph Trouillot most forcefully signaled the damning implications of eliding the world-historical significance of the Haitian Revolution in his well-known book Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History (Beacon, 1995). Trouillot insisted that the “silencing” of the Haitian Revolution (1791-1804) is only “a chapter within a narrative of global domination.” “It is part of the history of the West,” he said, “and it is likely to persist, even in attenuated form, as long as the history of the West is not retold in ways that bring forward the perspective of the world.” By erasing, downplaying, or otherwise denying how the Haitian revolutionaries opened the door to the Age of Abolition—when they proclaimed slavery an actual crime and declared that freedom from slavery should be constituted as a universal human right—it is not just Haitian history, but the Haitian people themselves who have been silenced.

The remarkable stories of some of Haiti’s most famous Black freedom-fighters, Dutty Boukman, Cécile Fatiman, Toussaint Louverture, Suzanne Bélair, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, and Henry Christophe, for example, have been replaced in the world’s memory by the more treacherous recent histories of dictatorships, earthquakes, presidential assassinations, and armed paramilitary violence. Moreover, in the nineteenth century, instead of garnering global applause, Haiti’s insistence on remaining free and independent consistently brought punishment, most aggressively, by France. In 1825, French king Charles X ensured longitudinal impoverishment of the newly independent country when he ordered the Haitian government, under threat of war, to pay 150 million francs as the price of France relinquishing its territorial claim over the island and to compensate former French enslavers for the loss of their “property.”

Bringing forward the perspective of Haitians represents one way to both lessen the silences of the past and rectify the ongoing and harmful distortions of the present. In my recently published biography, The First and Last King of Haiti: The Rise and Fall of Henry Christophe, I therefore sought to highlight the stories of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Haitians, whose numerous memoirs, pamphlets, letters, and myriad collections of essays and other forms of writing about the Haitian Revolution have often been ignored in favor of consulting western European and U.S. sources. At the same time, an incomplete and sometimes non-existent written archive encouraged me as a historian and literary critic to be imaginative in considering alternative sources about King Henry’s life, including oral histories, and to question the privileging of written forms over other kinds of storytelling.

The present list of books, then, all by Haitian authors, is a further attempt to contribute to Trouillot’s wish for the “perspective of the world” to be brought forward. Spanning nearly the entirety of Haiti’s history, from the period of colonization in the eighteenth century, to the revolution and war of independence in the nineteenth, to the U.S. occupation in the early twentieth, to Haitian women’s cultural contributions at the turn of the century, these books tell complicated and nuanced stories about Haiti and Haitians’ attempt to create a sovereign existence in a world where Black freedom has been endlessly under threat. [. . .]

[The First and Last King of Haiti: The Rise and Fall of Henry Christophe by Marlene L. Daut is a finalist for the 2025 Cundill History Prize.]

For full article, see https://lithub.com/five-essential-books-for-understanding-haitian-history

Marlene L. Daut (Yale University) reviews five essential books for understanding Haitian history. Visit Literary Hub to read the full article and summaries of these important works: Baron de Vastey, The Colonial System Unveiled (2014, Liverpool University Press); Jean Casimir, The Haitians: A Decolonial History (University of North Carolina Press, 2020); Louis Joseph Janvier, Haiti for the Haitians (Liverpool University Press);