EU officials are meeting today to discuss what would be a 20th sanctions package against Russia, focusing on the “shadow fleet” helping circumvent existing sanctions on Moscow’s oil and gas imports.

In the 19th package announced in October, the EU listed 557 vessels believed to be acting as a proxy for Russia in international waters.

What is the shadow fleet?

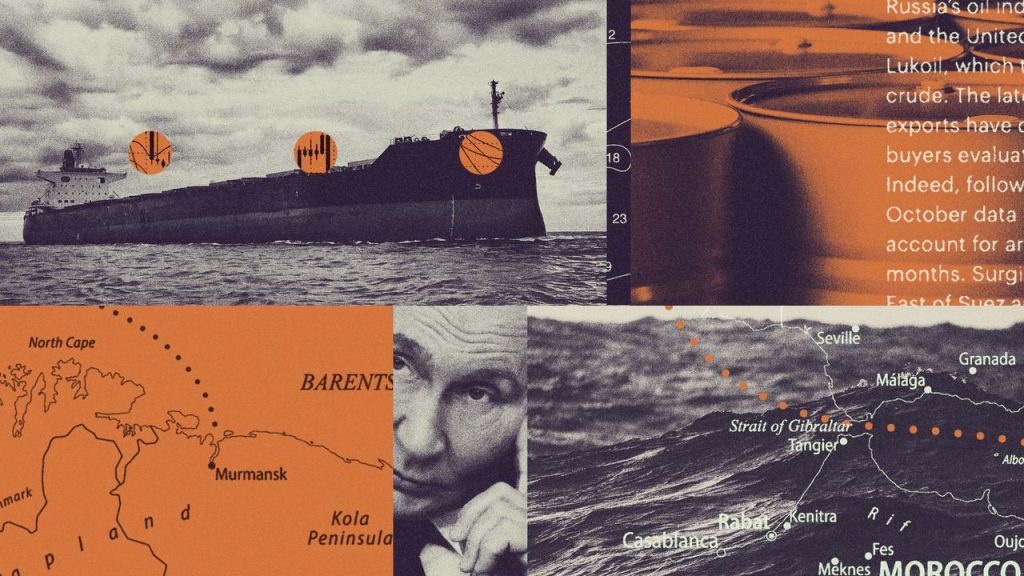

It refers to a group of largely Russian-owned vessels, usually tankers, that sail under various non-Russian flags. On board, they carry sanctioned commodities like oil to customers such as India and China, to bypass sanctions and export caps.

“Flag hopping” allows ships to “switch identities” by “jumping from one registry to another”, said The Parliament Magazine. Ships slip under the radar by “exploiting lenient registries” in countries such as Panama, Liberia and the Marshall Islands.

Over the last year in particular, it has become “so easy now to re-register somewhere else” that the practice has “escalated to an unprecedented peak”, leaving Russian tankers hiding in plain sight.

Analysis by the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air found that shadow tankers ship around 62% of Russia’s crude oil exports, which in October alone brought almost £10 billion into Kremlin coffers, said the BBC.

What other problems does it cause?

The issues around the shadow fleet are particularly acute in the Baltic region, which is seeing more such vessels pass through its waters, said The Guardian. Maritime areas around Finland and Sweden were seen as a potential “Nato lake” when the two countries joined the Western military alliance in 2023 and 2024 respectively, but they have since become a “battleground for hybrid warfare”.

In August, Finnish authorities filed charges against crew members of a tanker suspected of damaging undersea cables by dragging its anchor in December 2024. The damage was reported to cost the owners “at least €60 million” in repair costs, said The Guardian.

But unless there is tangible or substantial evidence of a crime – infringing environmental, fishing or sea traffic law – the Swedish and Finnish coastguards’ ability to act is “extremely limited”.

The issues go beyond violation of sanctions. Ships sailing without displaying or registering under a valid national flag are operating “without proper insurance”, said the BBC. If a major spill were to occur, the financial fallout and clean-up operation would be huge.

How can governments counter them?

Establishing jurisdiction is challenging. National law can only apply in a country’s territorial waters, usually defined as within 12 nautical miles of the coast. Further out to sea, “freedom of navigation is a golden rule”. National governments have neither the legal ability, nor political appetite, to risk “escalating” the issue.

One way of tackling the shadow fleet is to boost powers to board suspected vessels for inspection, said Politico. In a draft declaration prepared last month for a meeting of EU foreign ministers, the EU proposed “more robust enforcement actions tackling the shadow fleet”, including pre-authorised boarding of suspected shadow fleet vessels, supported by bilateral agreements.

The draft also offered incentives to flag states to deregister sanctioned vessels. This appears to be having an effect. Earlier this year, Panama, the largest ship registry, committed to rejecting bulk carriers over the age of 15 years, which are often used in shadow fleets as their provenance is harder to ascertain.

A growing number of uninsured and falsely registered vessels are entering international waters, dodging EU sanctions on Moscow’s oil and gas