Stone is “making a comeback” in the building industry after years of being “forgotten”, said the BBC. With clear benefits to the environment, such as a lower carbon footprint than other traditional materials, the substance’s popularity is growing as a more sustainable, and nostalgic, alternative.

In warmer climates, stone is valued for its cooling properties, but the benefits of stone in the UK could be much more varied.

‘Tangible link’ to the past

The rise in demand seems to be particularly welcome north of the border. Scotland’s identity is “closely linked to its stone-built heritage”, said Historic Environment Scotland. Stone infrastructure is not only a “tangible link” to the country’s past, but it also stimulates financial opportunities. Millions of tourists see stonework, and the traditional aesthetic of stone walls and buildings as a “huge draw”, and their arrival provides a “vital source of income” for local economies.

In rural areas, stone walling and stone building have long histories, dating as far back as 5,000 years, said Jennie Rothenberg Gritz in Smithsonian. Stonewalling uses stones, “carefully fitted together in such a way that the wall won’t fall down” without any mortar or cement. This means that if you have to fix one section, the whole wall remains secure, whereas “when a mortared wall cracks, the entire wall is in peril”.

“What price do you put on forever?”, stone wall expert Kristie de Garis told the magazine. “Mortared walls need to be redone roughly every 15 to 30 years. But there are dry stone walls still standing after thousands of years.”

‘Renaissance’ fuelled by sustainability

The most important aspect of stone is probably its “ecological value”, said Christiane Fath in World-Architects.com. Though it has always been popular and used in some of the most famous buildings in the world – think Cologne Cathedral, the Colosseum, or Notre Dame – in the era of climate change, stone is heading for a “renaissance” after major developments in Germany, specifically Cologne, Leipzig and Berlin.

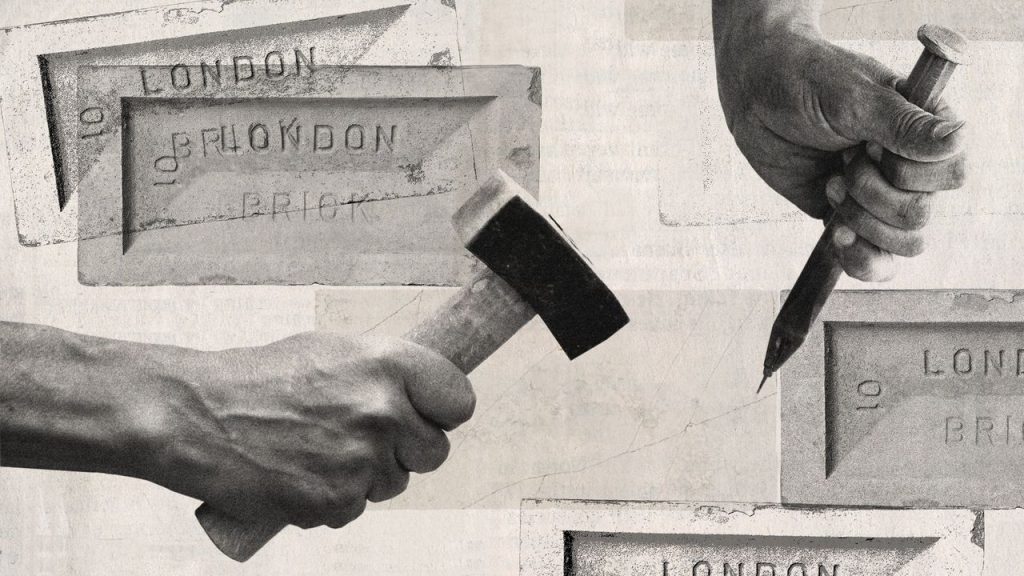

Its benefits are manifold, wrote Fath. Created by natural processes, its production “consumes little energy”, and its “buildings can be recycled” if approached intelligently. Stone building’s human input should not be overlooked: despite the use of machinery in its production, the creation of stone elements is still an “artisan process” providing “additional cultural value”, and is a celebration of timeless craftsmanship.

“Building in brick is increasingly unsustainable”, said Amy Frearson in the FT. Processing bricks involves additional ingredients like lime, sand, and cement, even before the “energy cost of firing and shipping”. Sustainability aside, stone is a way of “delivering the very local character that the government wants” when developing houses, something which is important to local councils.

One major drawback of turning to stone as a material is the problem of “perception”, said the broadsheet. Added to the higher cost, and despite its strong load-bearing capacity, stone has cultivated a “luxury surface finish” image. This drives stringent demand for “uniform varieties”, “leaving anything short of perfect to be rejected and creating a lot of surplus”.

With brick building becoming ‘increasingly unsustainable’, could a reversion to stone be the future?