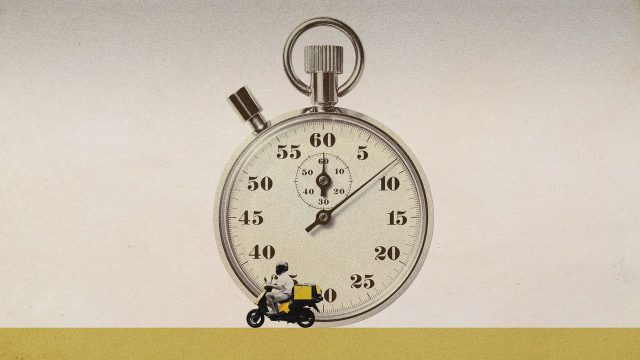

India’s “quick commerce” bubble may be about to burst, said the CEO of Blinkit, an app that promises delivery of orders within 10 minutes.

Albinder Dhindsa issued the warning as some competitors in the market are running on losses. He believes his company will thrive, but there has been unrest, and Blinkit’s riders took industrial action over pay and working conditions earlier in the year. The strike is just part of a wider crisis developing in India’s growing gig economy, where “speed trumps safety and workers are easily replaced”, said The Independent.

“The pendulum has already swung once from scepticism to exuberance,” Dhindsa told Bloomberg and believes he does not know when “correction” will come, but only that it will.

Dark stores

Blinkit allows customers to order groceries, fresh produce and daily essentials, which they expect to be delivered in around 10 minutes. To achieve this speedy turnaround, the platform relies on a network of “dark stores” – retail spaces that act as dedicated hubs for fulfilling online orders, rather than in-person shopping.

It forms part of India’s rapidly growing quick commerce sector, funded by investors attracted by the country’s “dense cities, lower cost of labour and ubiquitous digital payments”, said Bloomberg.

The company launched in 2013 as Grofers, but rebranded in 2021 as Blinkit, invoking the idea that service will happen “in the blink of an eye”. Acquired by the country’s food delivery giant Zomato in 2022, it’s now active in many cities across India, delivering “everything from eggs to iPhones” to a client base of millions.

But, it has yet to turn a profit, hampered by “capital costs and supply chain complexity” as it pursues further expansion, including into rural areas.

Straightforward demands

Earlier this year, more than 150 Blinkit workers in the city of Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh, went on a two-day strike to protest “unsafe working conditions, falling earnings, and retaliatory ID suspensions” (when gig platforms deactivate workers’ accounts without due process or a means of redress), said The Independent.

The striking riders had “straightforward demands”, including “weather-appropriate uniforms and shaded waiting areas” alongside an end to a “punishing rule that effectively forces them to work the hottest hours of the day”.

They also want the company to “restore the original incentive pay structure”. They are paid on a per-order basis, with “fluctuating incentives”, with terms having “ been quietly changed over time”. Riders claim that they used to receive Rs 555 (£4.93) per 32 orders delivered, but now earn just Rs 448 (£3.98) per 43, which means they are “doing more work for less”.

In November, the Indian government introduced new labour laws so that the fleet of self-employed workers will now receive social security, but they still have no right to a fixed wage or paid leave.

The April strike was a “flashpoint” but not the last in what is becoming a “growing struggle” between “speed-driven platforms” and the workers holding up a gig economy that’s forecast to employ over 23 million Indians by 2029.

Market pressures and rider unrest are casting a shadow over leading player