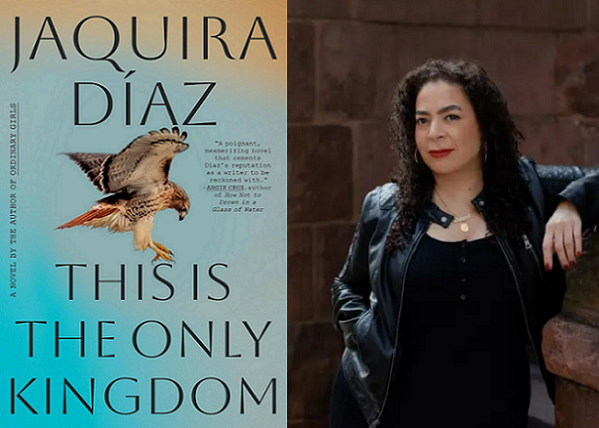

Evander Reyes (Electric Literature) interviews Jaquira Díaz, who speaks about her new novel This Is the Only Kingdom. Here are excerpts from his introduction and interview. Read the full article at Electric Lit. [Also see our previous post New Book: This is the Only Kingdom.]

Jaquira Díaz’s debut novel, This Is the Only Kingdom, begins with an epigraph drawn from Aracelis Girmay’s poem “Elegy”: “Listen to me. I am telling you a true thing. This is the only kingdom.” Girmay’s “kingdom” is not the afterlife or some promised utopia but the world as it is—the one we make and unmake together. The line is a plea to recognize the reality in front of us, the life we can touch, shape, and be held accountable for. Díaz makes this idea the moral engine of her novel, portraying characters who, despite living in a world steeped in tragedy, choose to inhabit it with the fullness and attention of those who understand how fragile it is to be alive.

The novel follows Maricarmen and her daughter Nena across decades as they reckon with loss, violence, and the harsh realities of life in a working-class barrio of Puerto Rico. Split into two parts, the first half focuses on Maricarmen and her forbidden love affair with the neighborhood’s Robin Hood-like figure, Rey. When he is killed by the police, Maricarmen is left to raise their daughter Nena alone. The second half, set fifteen years later, finds Maricarmen and Nena reckoning with the fallout of another brutal act of violence. Nena is forced to flee to Miami, where she must grow up fast and come to terms with her queer identity against the backdrop of the AIDS epidemic. Despite the weight of her circumstances, Nena begins to carve out a life of her own, finding in Miami’s queer community a model of care and connection that redefines what family means for her. Through all the grief and upheaval, Díaz’s streets and neighborhoods are alive with music, celebration, and the messy, often painful rhythms of life. This Is the Only Kingdom is an audacious debut that weaves intimate stories into the raw histories of homophobia, racism, poverty, and state violence. [. . .]

ER: Your novel takes its title from a line in a poem by Aracelis Girmay, which serves as the book’s epigraph. What drew you to that line, and how does the idea of the “only kingdom” shape the world and the lives of the characters you inhabit on the page?

JD: I returned to this poem after having read the poetry collection years ago. I came back to it after my mother’s death, which happened as I was writing this book. I was thinking a lot about interconnectedness and what it means to be alive and embodied, to have a physical body that we can touch and feel and embrace. That’s what we’re really grieving when we lose someone. That’s what I was grieving when I lost my mom: that I could not hug her, that I could not talk to her, that I could not be in her presence anymore. Our protagonist, Nena, is grieving someone she loves and is feeling that painful moment of I will never get to touch them again. I will never get to be in their presence again.

But the phrase also takes on other meanings. One has to do with the Catholic Church and how much it uses the word kingdom as a way of controlling people—explicitly telling queer people they’re not going to make it to the kingdom of heaven. The other has to do with colonialism and the U.S. relationship with Puerto Rico, and how the U.S. has become this power that controls Puerto Rico. People talk about Puerto Rico being a territory of the U.S., but this is all a myth. Puerto Rico is controlled by the U.S.

This book isn’t just about this family and these relationships; it’s also about the colonial relationship in which the U.S. controls Puerto Rico and every system within it, including the colonial project of el caserío—the housing projects in Puerto Rico—and how this system of poverty was designed and controlled by the U.S.

ER: In both your memoir and this book, you often return to the question of survival within broken systems and colonial legacies of poverty, family violence, structural violence, and displacement. In many ways, your work refuses the myth of escape from those realities—again, recalling Girmay’s line, “this is the only kingdom.” Instead, your work insists on staying with the truth of lived experience—no matter how difficult—and on finding beauty and meaning within it. What allows you to keep writing toward that truth, even when it’s painful?

JD: Writing has been a way of freeing myself. Rejecting the publishing machine’s ideas of what I should be writing has also been freeing. It’s been a way of knowing myself and navigating the world. Ordinary Girls and This Is the Only Kingdom have forced me to look at myself with curiosity and humility, at how I exist within my own family, within these systems, and in the world. I’ve had to acknowledge the ways I’m complicit in these things: the way I live in the U.S., get to return to Puerto Rico, and spend time with my family who have to live with the real-life consequences of colonialism. I get to return to my home in New York and write about it. I acknowledge all the ways I have more power and more resources than they do. Yes, it’s a privilege. But I also don’t want to be in the U.S. I want to live in Puerto Rico. I want to make a living and raise a family there. Displacement is very real for me. It feels like a kind of exile. Even though I can return, the life I want isn’t the one I have here. I want the life my family has over there and to live fully in my community. And yet I don’t feel like that’s possible. For many of us in the diaspora, there’s always this longing, this nostalgia to go back. I’m always contending with that as I write. [. . .]

Read full article at https://electricliterature.com/a-novel-about-building-queer-community-after-harm/ (Thanks, Sabina!)

Also see https://electricliterature.com/a-novel-about-building-queer-community-after-harm/ and our previous post https://repeatingislands.com/2025/11/01/new-book-this-is-the-only-kingdom/

Evander Reyes (Electric Literature) interviews Jaquira Díaz, who speaks about her new novel This Is the Only Kingdom. Here are excerpts from his introduction and interview. Read the full article at Electric Lit. [Also see our previous post New Book: This is the Only Kingdom.] Jaquira Díaz’s debut novel, This Is the Only Kingdom, begins with