During her lifetime, Gwen John’s achievements were rather overshadowed by those of her younger brother Augustus, said Jonathan Jones in The Guardian. Today, though, she is arguably Wales’ most famous artist – and, to mark the 150th anniversary of her birth in 1876, she is now the subject of this “superb, daunting” retrospective in Cardiff. It does not give us a blow by blow biography of the artist, who grew up in Haverfordwest and followed her brother to the Slade art school, before moving to France. Instead, the show plunges us straight into her “spiritual, austere existence”.

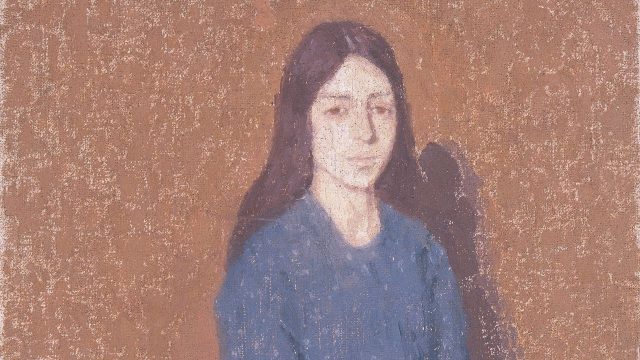

We meet John in Paris, painting cats, the sparse rooms she rented “and women alone in moments of calm thought”. In a series started in the early 1910s, a young woman in a blue dress – a convalescent – sits “weakly in an armchair”. The brilliance of these canvases lies in what they do not show; there are no “chatting crowds”, no gaudy hats, no omnibuses. In her work, John cut out the “social flab”, to focus on the inner experience – in this case, a woman’s “sorrow, illness, despair, recovery”. It is not that she is an artist without passion or desire (she had a decade-long affair with the sculptor Auguste Rodin); it’s simply that in her quest to escape the repressive dishonesty of the world into which she was born, she stripped it all back, and painted only what was essential.

John’s subject matter never deviated far from those paintings, but her style developed over the years, said Alastair Smart in The Telegraph. In 1897’s “Young Woman Playing a Violin”, “attention is paid even to the strings” on the bow. A couple of decades later, influenced by James McNeill Whistler, John’s work has become more ethereal. Aided by the pioneering application of a mix of chalk and animal glue to her canvases, figures such as the praying woman in “The Pilgrim” “seem weightless, almost levitating off the canvas towards us”. But though these latter works are “riveting”, they are not enough to sustain a show of this size. Of the 200 pieces here, too many are rarely shown works on paper – dreary watercolours of nuns, cats and flowers. Their inclusion reinforces the sense that John was a limited artist, a little of whom “goes a long way”.

Some of these works are admittedly weak, said Laura Cumming in The Observer, but the focus of the show is John’s method: how she created, for instance, atmosphere and a sense of presence in empty rooms. One of her best-loved paintings, “A Corner of the Artist’s Room in Paris” (c.1907-09), has light filtering in through a curtain and a parasol leaning “against a chair drawn comfortingly close” to a table that is bare save for some flowers, it’s “still, quiet, calm” – a sanctuary for the viewer, too. But then we see a second painting of the same corner. Now the curtain is part open; John has taken a step back; the tones are sharper. This painting feels active. The room is not changed; what has altered is the state of her mind, or of her heart.

National Museum Cardiff. Until 28 June.

‘Daunting’ show at the National Museum Cardiff plunges viewers into the Welsh artist’s ‘spiritual, austere existence’