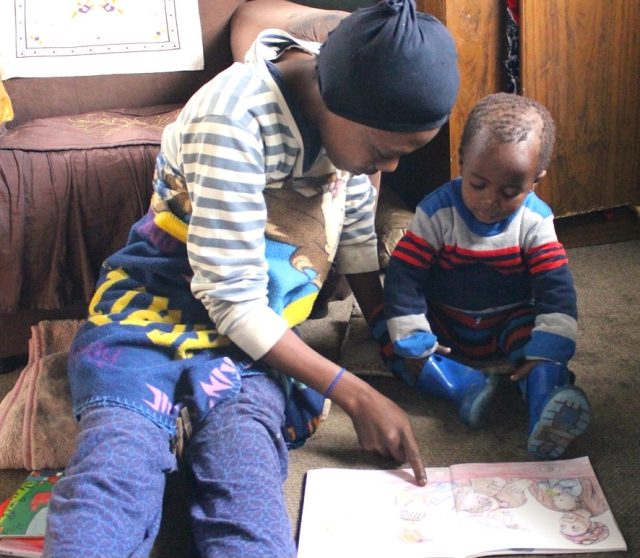

In the Masete household in Ghost Town, Makhanda, a young granddaughter, Enzokuhle, holds a baby and a book, confidently reading aloud to her siblings and cousins.

It wasn’t always like this. Reading once felt like a chore, something uncomfortable and unfamiliar.

“It was a miracle,” Nokuzola Masete recalls, summoning a video from her phone as proof of the transformation that began with a simple parcel of books dropped at their gate during the height of Covid restrictions. She watches with pride as her granddaughter turns pages effortlessly, even before starting school.

Campaign takes flight

The Lebone Centre’s “20 books in 200 homes in 2020” campaign delivered carefully curated, age-and language-appropriate books to enigmatically named communities, including Sun City, Ghost Town, Scott’s Farm, and Vergenoeg.

The campaign drew from a 2010 longitudinal study of 27 nations by Professor Mariah Evans and her colleagues, which showed that children growing up in homes with books receive three years more schooling than children from bookless homes, independent of their parents’ education, occupation and class.

The researchers discovered this was as great an advantage as having university-educated rather than unschooled parents and twice the benefit of having a professional rather than an unskilled father.

It holds equally “in rich nations and in poor; in the past and in the present; under communism, capitalism, and apartheid”, the study concluded. Homes with at least 20 books provided a “tipping point” for literacy development, with benefits increasing in proportion to the number of books.

Twenty books per household was Lebone’s initial target.

Once Covid-19 restrictions eased, Lebone staff, like home visitor Kaylynne Rushin, sanitised books and their hands before delivering packages to gates in neighbourhoods where books were scarce and literacy practices rare.

Families watched from afar, but the seeds were planted. By 2022/23, the project had deepened, focusing on 50 of the original homes with follow-ups, training and resources, sparking lasting literacy habits.

Masete describes how the centre’s advice to parents on helping children read built confidence and routine.

Reading evolved from a burden to a daily joy, with her granddaughter not only reading independently but sharing stories with others.

“After Lebone gave us the books, they didn’t just disappear. They follow up with the kids as well as the parents.”

“We’re going to cry if we lose Lebone,” she says. “It was life-changing … Other parents must not take this project like a piece of paper. They must take it seriously and intervene because it has opened our minds and our children’s minds.”

The fieldworker’s story

Fieldworker Rushin notes initial hurdles: parents feeling inadequate due to their own educational backgrounds, especially in informal settlements. Through patient training on book sharing, the barriers dissolved, fostering stronger relationships and increased confidence.

Rushin’s family story mirrors this: her eight-year-old daughter was “over the moon” upon receiving a package, deciding to open a home library and share books with her siblings, aged two and 10.

“I really believe that this one book package will help all my children prosper in their education, especially their reading, literacy and language skills,” Rushin says.

In another home, Katryne Maphele’s story echoes this evolution. Early attempts at teaching her children sparked fights as they resisted her efforts. Persistence paid off; now, Selunathi, Libanathi and Luminathi read daily at 5.30pm, even in her absence.

Her advice to fellow parents? “Do not be tired. You must have patience with the kids.”

The children light up as they recount tales from Lefa’s Bath and Goldilocks and the Three Bears. They discuss lessons learnt: “Do not be mean; be kind, and be clever and sweet.” They love discovering new words, studying pictures to fuel their imagination and sharing their reading adventures with others.

Building parents’ confidence

The approach shows that with the right resources and guidance, families can become powerful partners in their children’s literacy journey.

Yet Rushin reveals a common hurdle: “Some of the parents think they are not good enough to teach their children, depending on their educational background.”

This reluctance is transformed through patient intervention.

“When we come, we give them the skills, we give them training and teach them about book sharing; then they gain more confidence about sitting with their children with books.

“In some homes, especially in the more informal settlements, we needed to gain people’s trust because it’s not a good feeling for someone to admit that they can’t read or can’t write. As the time grew, I really built some good relationships in the community and earned people’s trust.”

Lebone’s fieldworkers approach their mission with patience, perseverance and unwavering commitment. They understand the transformative power of literacy in families. Books deepen family relationships and are gateways to meaning-making and world-understanding.

Pre-school literacy scaffolding

Globally, debates rage around how children learn to read (sometimes referred to as the “literacy wars”), but this detracts from the essential steps of moving children into the next phase of reading for meaning, understanding and enjoyment.

What children need in the early years of their literacy development is scaffolding — the fine network of support that surrounds the technical skills of learning to read and write: the reading and telling of stories, the singing of nursery rhymes, creating access to books, modelling reading behaviour, sparking imagination and joy, creating safe spaces and pleasurable connotations of sharing and attachment.

Much of the scaffolding needs to take place in homes and community spaces, as there is often little time, capacity or willingness to provide it in schools, especially in overcrowded classrooms with few or no reading resources.

The 2016 and 2021 PIRLS Reports reinforced this, linking higher test achievements to more home books and parental involvement, amid South Africa’s stark reality where 81% of Grade 4 pupils couldn’t read for meaning.

Reading versus literacy

Too many parents hold the misconception that literacy support begins and ends with reading, leaving Foundation Phase teachers to shoulder the burden. Yet children require the foundational support during their earliest developmental stages to arrive at the Foundation Phase prepared for learning.

“The ‘Creating Communities of Readers’ project successfully accompanied these families on a journey towards believing in the value of reading and being more knowledgeable and confident about sharing books with their young children,” said Dr Shelley O’Carroll, who evaluated the Lebone project in 2024.

“The majority of caregivers and parents were reading more, but also spending more time telling stories and playing. There was also a marked increase in time spent engaging in drawing and writing activities. It was evident that books sparked new reading habits, with many parents and caregivers inspired to read more and requesting more adult reading materials,” she wrote.

The high impact of simple, low-cost strategies

As a relatively low-cost intervention, Lebone’s home-based literacy initiative confirmed the value of simple strategies, such as providing the right resources and meeting parents where they are.

Lebone targeted poorer homes with few or no books. And yet, there was a hunger for reading resources and a willingness to participate.

Masete is proud of how reading as a daily habit joyfully enhanced her granddaughter’s early development. The shift from an uncomfortable task to a pleasurable routine demonstrates how targeted support can transform literacy cultures in families — and, eventually, wider communities.

Who’s who in home literacy in South Africa?

Other organisations that work in the home and community are:

- Nal’ibali (nalibali.org) emphasises the production of story and reading resources in all of the South African languages. Provincial teams mobilise communities, conduct caregiver training, run home visits, distribute multilingual reading materials, encourage library membership and establish reading clubs that involve families directly. All these activities create a bridge between schools, communities, and homes.

- Book Dash (bookdash.org) emphasises child book ownership for young children.

- Mikhulu Trust (mikulutrust.org) focuses on parent-child book-sharing.

- Wordworks (wordworks.org) focuses on early literacy stimulation.

- Programs like READ Educational Trust’s family literacy modules (spanning seven sessions over two years, emphasizing play), the Family Literacy Project (using REFLECT for adult literacy and child-to-child sessions in rural KwaZulu-Natal), Project Literacy’s Run Home to Read (training low-literacy parents to read storybooks), and ELRU’s Family and Community Motivators (empowering caregivers with child development guidance and home visits) demonstrate diverse approaches, often showing improved child literacy, parental confidence, and home-school bonds.

This feature was made possible by the Henry Nxumalo Foundation which funded the literacy project.

Children growing up in homes with many books receive three years more schooling than children from bookless homes, a study shows