By 2023, after enduring persistent water outages, Archie Sooliman* had enough. The homeowner in the upmarket Johannesburg suburb of Greenside decided to install a borehole.

It cost about R60 000, but he has no regrets. “We put it in when we were having these major water cuts where we were out for days, like two days and three days at a time,” he said. “Water just became such an issue.”

Boreholes are mushrooming in the area, said Sooliman, who counted four on his street alone. “In Emmarentia, every second day, you see a drilling truck drilling a borehole. There’s a database of houses in the area that have boreholes and during water cuts … you can ask your neighbours for water.”

His family uses their borehole water for showering, running toilets and to wash dishes during municipal supply cuts. Sooliman has since installed a three-stage filtration system for drinking purposes.

“It’s like [installing] solar when Eskom wasn’t giving us electricity, we were, like, let’s just get solar; let’s just look after ourselves and be self-sufficient. When the municipal water [supply] is fine, we just switch over to municipal water.”

Every night, his suburb is hit with water throttling. Two weeks ago, there was no water in Greenside for four days. “The people who live in the higher areas in Emmarentia didn’t have water for six or seven days.”

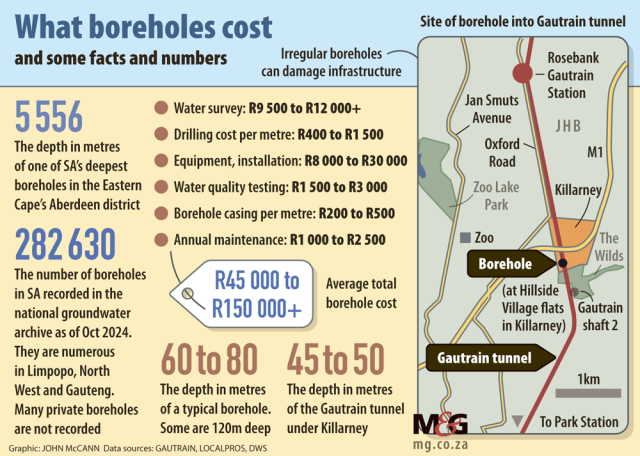

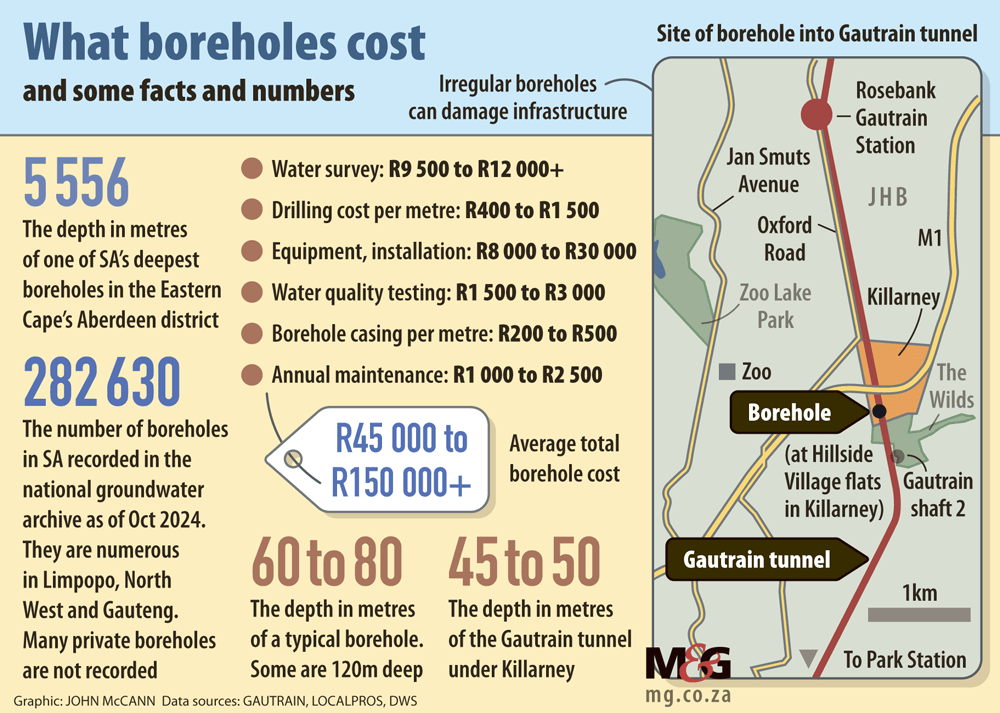

Water scientist Ayesha Laher said more and more, those who can afford it are opting for this alternative water source, to alleviate the deepening water crisis in Johannesburg. The cost of drilling a borehole at a home is R50 000 to R120 000.

“Anybody will do that to keep their businesses and homes running because there are areas that have 15 or 20 days without water,” she said.

“They cannot sustain themselves… What they end up doing is drilling a borehole and saying, ‘I’m going to help my neighbours and give everyone around me water.’”

But groundwater is a limited resource.

“If you don’t use it sustainably, you end up with a lot of associated potential risks. One would be that you drain the aquifer dry and then you have a hole in the bottom of the ground,” Laher said.

“The consequence of that is anything from you drilling into the Gautrain station to perhaps hitting a dolomite area and the ground caving in. You could drill a borehole and hit an acid mine drainage vein and it will bubble to the surface.”

The issue everyone is grappling with in Gauteng’s cities is, “if you are sustainably using water from an aquifer, but there are 300 additional people also drilling and taking water from the same aquifer, you will have an issue where the aquifer is going to be depleted or you could possibly have ingress of contaminants from an adjacent aquifer”, she said.

Last month, unauthorised borehole drilling on private property caused the suspension of Gautrain services between Park Station and Rosebank, public broadcaster SABC reported. This illegal drilling caused soil and water to leak into the tunnel, and the Gautrain Management Agency has since taken legal action against the body corporate of Hillside Village, an apartment complex in Killarney near The Wilds.

The city’s member of the mayoral committee for public safety, Mgcini Tshwaku, noted that people were arrested recently while drilling a borehole in the city centre, while others were apprehended after drilling a borehole in the suburb of Mayfair.

“All those found drilling without approval will be arrested, their equipment confiscated and they will face the full might of the law,” he said.

Regulations and by-laws govern the drilling of boreholes in terms of the city’s Land Use Scheme of 2018, Section 41, which requires a written consent application to be submitted to the city, Johannesburg spokesperson Virgil James said.

“An application is processed and considered within 28 days from the date of submission of the complete application. If the written application process is not followed, then we will not be aware of illegal boreholes until reported or noticed by law enforcement officers.

“We urge people not to drill without municipal permission to prevent possible disastrous incidents.”

The record of applications submitted for borehole written consent are registered and kept on the town planning application system and this information is not publicly available, he added.

“Since the Gautrain incident, we are on alert and urge the reporting of borehole drilling in case it is an illegal drill,” James said.

Asked whether there’s a marked increase in borehole drilling in Johannesburg, he said the city was unable to confirm this “unless we receive a sudden and notable increase in applications”.

According to Anja du Plessis, an associate professor at the University of South Africa and a specialist in water resource management, “everyone is drilling boreholes over the whole of Johannesburg and Gauteng in desperation to become more water-resilient”.

For businesses, tapping into this water supply is an attempt to recover the economic and financial losses they experience from water throttling, water-shedding, frequent pipe bursts or from unpreparedness and poor maintenance by Rand Water.

“There should be concern about the amount of boreholes being drilled all over the show; we do not know the amount of water that is being removed because it’s not being metered or monitored. There’s no regulation of that by the city because there’s no clear compliance and regulations,” Du Plessis said.

“Most people don’t know that they even have to register a borehole.”

Sooliman admitted that when his installer asked whether he should register his borehole, he refused. “I was like, bugger them, they’re not giving us the service, we have to look after ourselves, it costs us money.”

The effects of excessive abstraction will be seen in the water table, Du Plessis said. “You will only know when your borehole is dry — I’ve heard in the Sandton area, those boreholes have actually run dry; some of them are flowing again now.”

Boreholes are “not a silver bullet” for water resilience or to try to become less dependent on municipality supply, she added.

Du Plessis draws comparisons with the rising trend to install solar due to the load-shedding crisis.

“It’s almost like the solar situation where every single cowboy could put solar on and then you heard of people’s houses burning down.”

The same cowboy attitude is unfolding with boreholes.

“Everyone is drilling, whether they are actually doing surveys to say, ‘You know what, it is not cost effective for you to drill a borehole.’ In Craighall Park some of them have to drill past 120 metres — that is a lot of money and the amount of water that they get from that is not even a lot.”

Back-up water tanks and boreholes are symptomatic of the water problems in Johannesburg and in the wider province, said Laher. “Water is life. You can stay without electricity but you cannot stay without bathing for two days and flushing away your sewage.”

Water tank sales are also rising. Water solutions company JoJo said since 2021, it has experienced a steady growth in the Gauteng region with a significant surge in demand from early 2023.

This growth extends beyond water tanks to comprehensive water solutions, including pumps, filtration systems and related accessories, according to Julien Smith, JoJo’s acting national sales and marketing executive.

Growth in the Gauteng market has consistently remained in the “double-digit range”, he said. Given the increasing demand in water-stressed areas, the company’s best-selling products in the region are its 1 000-litre Slimline water tank, the 2 400-litre water tank and the 5 250-litre water tank. “Additionally, our range of filtration products, pumps and connector kits continues to complement these tanks, further supporting consumer needs. The demand for water solutions is expected to continue on an upward trajectory as more consumers take steps to ensure water security,” he said. Consumers are becoming increasingly “water-savvy”, incorporating rainwater harvesting for both drinking and irrigation purposes, he added.

But, said Du Plessis, those people who connect municipal water to their water tanks are “exacerbating the problem two-fold” because they are depleting the municipal water. “It’s not fair to those who are sitting at the top of the hill that have to wait for pressure to build up and for those who are last in line in the water reticulation system.”

“If you want to be selfish and say, ‘I’m going to put five JoJo tanks in my yard, I’m going to connect to municipal supply, I pay for the water and I don’t care about [other people],’ that’s human nature. But it’s not wise for the system.”

Ferrial Adam, the executive director of WaterCAN, a network of citizen science water activists, agreed.

“When there’s water cuts and then the water comes back, the water first fills the tank if you are using municipal water to fill up your tank. If you are filling up the tank first at your house, that means that other people are affected; that means that the water is going [down] much faster.

“What this then feeds is the high-demand scenario and then more people have less water, especially in the high-lying areas.”

* Not his real name.

The water crisis is driving a proliferation of boreholes and water tanks that can deplete the aquifer, cause contamination or acid mine drainage – or hit the Gautrain tunnel